World Series Cricket

A brief overview of World Series Cricket

Martin Williamson

10-Oct-2006

|

|

|

In May 1977 the cricketing establishment was shaken to the core with the announcement that Kerry Packer, an Australian media magnate, had signed more than three dozen of the world's leading players for a rival tournament to run head-to-head with the 1977-78 Australian season.

The series originated because Packer's attempts to secure TV rights for his Channel Nine network had been dismissed by the Australian Cricket Board in favour of a long-standing, and some said far too cosy, relationship with state broadcaster the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). Packer set about using his corporate wealth to establish a rival attraction for his network, a job made easier by the poor financial rewards offered to players at the time.

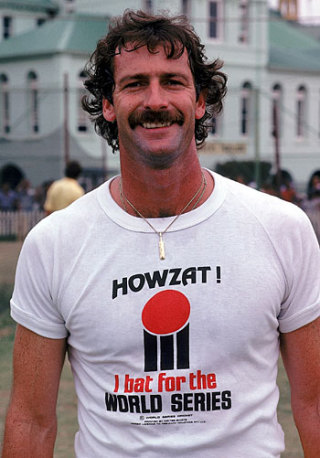

Through the second half of 1976 and early 1977 Packer signed up dozens of leading players, and remarkably the secret was kept until the eve of the official announcement. Packer's main agents were Tony Greig, at the time the England captain, and Ian Chappell, the former Australian captain, who did the bulk of the local recruitment.

The news broke on May 9, 1977 as the Australians prepared for their Ashes series in England - 13 of the 17 had signed for Packer. The media reaction was generally unwelcoming while the establishment were unable to hide their fury. World Series Cricket soon became known as Packer's Circus, Greig was stripped of the England captaincy, and was singled out for vitriolic attacks by the press, while many wanted all those who had signed banned from playing anywhere. Over the summer more signings emerged, while Australia, a far from happy side, lost the series and the Ashes 3-0.

Packer had undertaken a PR offensive in the UK in May and June 1977 and while many regarded him as cricket's antichrist, there was no denying his passion and eloquence. Against a slick media operator, the cricketing establishment looked like floundering dinosaurs. His cause was further aided by signing the highly-regarded Richie Benaud as his advisor.

The ICC as slow to respond to what it initially saw as an Australian affair, but as recruiting increased it became apparent WSC affected the game across the world. The ICC met with Packer in London on June 23. Initially, it seemed that the two sides might reach agreement but talks broke down over Packer's insistence that Channel Nine be awarded TV rights for the 1978-79 season. That was outside the ICC's powers. Packer stormed out with a clear message: "It's every man for himself and the devil take the hindmost."

Those comments polarised opinion and fired up the establishment. In July the ICC ruled that any Packer matches were not first-class and that anyone taking part would be banned from first-class and Test cricket.

For a while many players wavered. Packer acted quickly to protect his interests and launched his lawyers against boards and the ICC. Greig, Mike Procter and John Snow, backed by Packer, took the Test and County Cricket Board (TCCB - the forerunner of the ECB) to the High Court claiming restraint of trade.

For seven weeks from September 26, 1977, the case was played out with massive global interest. Packer claimed the ICC had tried to force his players to break contracts. On November 26m, Justice Slade delivered his verdict, finding for the plaintiffs, arguing that professional cricketers need to make a living and the ICC was wrong to stand in the way just because its own interests may be damaged. The cost to the establishment was close to £250,000 as costs were awarded against them.

Not everything went Packer's way. He was barred from describing the games as "Test matches" nor could he call the side "Australia". He rebranded the games "Supertests" and the team "WSC Australia XI". Such was the take-up among West Indies players that Packer was able to add a third team - WSC West Indies XI - to his tournament, although some of these players doubled up for the WSC World XI which rather tarnished the credibility of the matches.

|

|

|

He was also locked out of the traditional grounds, having to lease non-cricket stadiums in the major cities. The authorities thought that would undermine the standards as those venues did not have cricket squares, but Packer's groundsman, John Maley, devised drop-in pitches. Grown in greenhouses, they saved WSC, despite initial scepticism.

Some players were barred from grade cricket - Ray Bright was forced to keep in touch by playing for Footscray Technical College, Richie Robinson for North Alphington.

On November 24, 1977, two trial matches took place without major hiccups, and on December 2, 1977 the first official Supertest between Australia and West Indies got underway at Melbourne 's VFL Park. To the delight of the establishment, attendances were derisory, with barely 2000 people in the vast 79,000-capacity venue. What's more, the crowds at the official Test between what amounted to a second-string Australia side and India were good.

The imbalance was short lived. Packer poured money into marketing and advertising, using established names to back the media push. It was all about big hitting and fast bowlers. Spinners or grafters hardly got a look in. It was brutal , especially for the batsmen who were subjected to a bouncer barrage - WSC even removed the ban on bowling short at tail enders. Within weeks extra protective equipment started appearing, and horrific broken jaw suffered by David Hookes at the hands of Andy Roberts only served to speed the arrival of helmets.

Packer also changed tack from Supertests to one-day cricket. Again, initial response was lukewarm, although day-night matches had shown a more healthy turnout. It was to help shape the second season.

The Australian media had, by and large, sided with the board and so WSC was fighting on two fronts - cricket and media. What is more, the official Australia side, under the recalled veteran Bobby Simpson, had a gripping 3-2 series win over India, who had no Packer defections to content with.

The first cracks in the establishment hardline came in March 1978 when Simpson's young side headed to the Caribbean. With the WSC season finished, the West Indies board picked their full-strength side, including all Packer's rebels.

While England refused to pick their rebels - Greig, Derek Underwood, Alan Knott and Bob Woolmer - in the 1978 summer, many WSC-contracted players turned out in county cricket. Pakistan also refused to pick Packer players but relaxed when more players were signed between seasons. The other main World XI contingent came from politically-isolated South Africa, with New Zealand and India unaffected.

|

|

|

Packer used the off-season to sign more players - at the peak there were more than four dozen - and rumours grew that he planned to field two more full XIs from England and Pakistan. So many players were contracted that a second-string WSC tour was arranged to take the game to outlying areas of Australia. The side, led by Eddie Barlow, was called the Cavaliers and featured a mix of recently-retired and up-and-coming players. Packer also organized a short tour to New Zealand and a much more substantial one to West Indies in the spring of 1978-79.

Ahead of the 1978-79 season WSC finally got a foothold inside the establishment camp with an agreement from the New South Wales government that he could use the SCG, complete with newly-installed lights, and soon after WSC gained access to the Gabba. Perth and Adelaide were jettisoned from the itinerary and WSC concentrated on the population centres of Sydney and Melbourne.

Without doubt, the Australian Cricket Board had won the 1977-78 war. However, it was thumped the following season. The official side, now under Graham Yallop, were trounced by Mike Brearley's England five Tests to one in a fairly turgid series, while WSC's day-night cricket, after a slow start, really caught the public's imagination. On November 28, 1978 a crowd of 44,377 watched Packer's Australian and West Indies side play at the SCG - the first floodlit game at a traditional venue. The drubbings of Yallops side also swung the media who now demanded the return of the Packer defectors to bolster the side.

Packer's marketing also hit home, targeting women and children. By the end of the summer it was clear that the ACB were on the back foot. The final Supertest between Australia and the World attracted 40,000 over three days; the final official Test 22,000 over four days. Desperate to redress the imbalance, the ACB hastily scheduled two Tests against Pakistan, who fielded their Packer rebels.

The WSC circus then upped and headed to the Caribbean for a series that was remorseless on the field and fiery off it. The five Supertests and 12 ODIs were popular with the public and, most importantly to the region, bailed the West Indies board out of a financial hole.

At the end of the season the ACB was hemorrhaging cash and goodwill. Its finances were limited and at risk of being reduced by WSC while Packer continued to pour money into his project. During March the two parties started a series of meetings that resulted in an announcement of a truce on May 30, 1979. It was clear who had won. Channel Nine had not only gained the rights to broadcast Australian cricket but Packer was granted a ten-year deal to promote and market the game. While the news was received with relief in Australia, the ICC and TCCB, which had taken a hard line in backing the ACB, felt they had been sold out.

If there was an uneasy peace at the top, the players were not all as happy, especially the Australians who feared they would be victimised by their board. The signs were not good when the ACB's World Cup team contained not one WSC player, and later in the year the squad to tour India was equally sans rebels. Kim Hughes, who led the two sides, paid a price as in many people's minds he became the face of the establishment.

By the time England toured for another hastily-arranged tour in 1979-80 - with the Ashes not at stake much to the ACB's anger - Greg Chappell was back in charge and WSC players were in the team. Learning from WSC, the ACB added many more ODIs and those, dotted between two concurrent three-Test series against England and West Indies , caused much unease. Crucially, it made the ACB a profit. The new era had arrived and Packer's influence, via the marketing and promotions contract, was there for all to see.

Martin Williamson is executive editor of Cricinfo