When they were kings

South Africa's 4-0 clean sweep of Australia in 1969-70 showcased some of the game's all-time greats yet none of them ever played Test cricket again

Rodney Hartman

29-Dec-2005

| ||

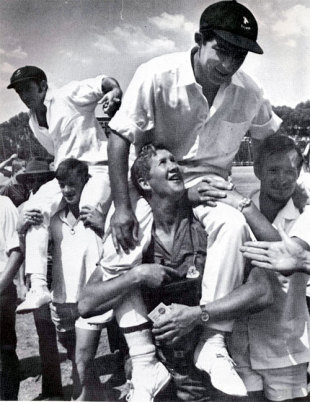

By clean-sweeping an Australian side who had won six and lost only one of its previous nine Tests, the 1969-70 cricket Springboks (as all South Africa's sports team were known up to 1991) left a legacy that no subsequent South African side has matched.

These players, at the peak of their powers, then left Test cricket for good. The golden age of Springbok cricket was summarily ended by the apartheid policies of the South African government.

South Africa's extraordinary run of success was played out against the backdrop of growing concerns about the advisability of the team touring England later that year. At the start of the Test series the Springbok rugby side were touring Britain, besieged at every turn by often violent anti-apartheid demonstrators. As the rugby players felt the force of growing anti-South African sentiment so support for the high-riding cricketers grew back home. These feelings were indicative of white South Africa's obsession to engage and conquer the world in sporting battle.

Sensing that a sports boycott was about to shut them out and starve them of top sporting action, the South African public flocked to the Tests against Australia. They had been without Test cricket for three years since the 3-1 triumph over Bob Simpson's Australians in 1966-67. So the matches were played to capacity crowds and, such was the frenzy of interest around the series, newspapers reserved front-page slots for it on a daily basis.

The crowds were of course racially segregated in line with the Separate Amenities Act, one of the draconian laws that underpinned apartheid. Blacks still turned out in numbers, particularly in Cape Town and Durban, but it was noticeable that many of them supported the Australians. The white fans relished the Springboks' dominance and gave the Aussies, particularly their unpopular captain Bill Lawry and Ian Chappell, a hard time.

The political noose tightening around South Africa's neck seemed to be a motivating force for its cricketers. The Springbok cricketers were united in the need to win - and win big - for the sake of their country. This was not politically inspired because the cricketers were increasingly incensed at being victims of apartheid. It was more their way of demonstrating that, in spite of apartheid, the world could not turn its back on them.

This stimulation was heightened by a team that, at its core, boasted the world-class talents of Graeme Pollock, Eddie Barlow, Mike Procter, Peter Pollock and the wicketkeeper Denis Lindsay (whose obituary will appear in next month's issue). And then there was a young opening batsman called Barry Richards who instantly took the cricket world by storm. In those four Tests - the only ones he ever played - he scored 508 runs at 72.57. John Arlott described him as "a batsman of staggering talent". To Ali Bacher, the South African captain in 1969-70, he was "the most complete batsman I ever encountered".

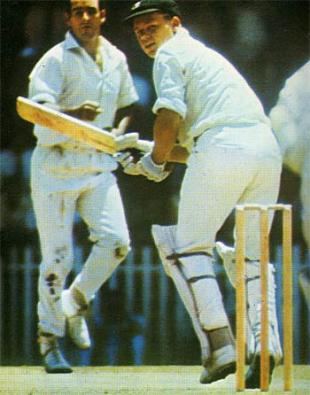

Richards was tall and elegant. He was still at the crease, saw the ball earlier than anyone and used his wrists to perfection. He had the potential to become one of the all-time great Test batsmen.

He scored nine of his 80 first-class centuries before lunch and, in the second Test at Durban, reached his maiden Test century against these Australians in the first over after lunch on the first day. If there was one passage of play that characterised South Africa's dominance it was in that hour after lunch at Kingsmead on February 5, 1970 when Richards and Graeme Pollock put on 103 runs in 60 minutes.

Richards was tall and elegant. He was still at the crease, saw the ball earlier than anyone and used his wrists to perfection. He had the potential to become one of the all-time great Test batsmen

Richards, 24, made 94 out of 126 for 2 at lunch. He had scored 140 of the 229 runs on the board before he lifted his head and was bowled by Eric Freeman. His hundred had come off 116 balls.

Pollock, the left-handed genius in his 21st Test, batted on for another six hours to reach 274, then the highest by a South African in Tests, before hitting a tired return catch to Keith Stackpole. Pollock's imperious batsmanship had brought him 177 runs in boundaries and those lucky enough to be in the ground were united in the belief that political obstacles could not be allowed to obstruct players of such pure box-office potential.

Pollock was the broadsword to Richards' rapier. He was one of the first players to use a heavy bat and he crashed anything loose on either side of the wicket. His cover drive was his signature shot but he developed an equally lethal pull and on-drive to overcome an apparent leg-side weakness early in his career. "One thing that was absolutely certain about Graeme," recalls Ali Bacher, "was that if you bowled a bad ball to him, it went for four." Don Bradman remarked at the time simply that Pollock was the best left-hander he had seen.

South Africa were a team of stars and few shone as brightly as Eddie Barlow, the bespectacled and rotund allrounder. He was the most belligerent and confident Springbok of all and known to his team-mates as `Bunter'. He had wanted to be the captain and had the support of many pundits but Bacher, his great rival, got the nod. At Durban Barlow made only one after coming in at 229 for 3 at the dismissal of Richards. He explained there was "no price" batting after Richards and Pollock.

In the second innings, after Bacher (a medical doctor) had enforced the follow-on with a 465-run advantage, the Aussies were mounting a fightback when a telegram was delivered to the captain on the field. It read: "Please Doc, give me a bowl. Bunter." Bacher tossed him the ball. Barlow, whose figures were 0 for 50 at the time, rolled in, medium-fast and took three wickets in 11 balls.

| ||

Unusually for Australia there were also rumours (which turned out to be true) of rifts in the touring party over the captain's autocratic style of leadership. At the start of the tour he described his vice-captain Ian Chappell as "the best batsman in the world in any conditions". In South Africa Chappell averaged 11.50 in eight innings with a top score of 34.

Chappell's problems were symptomatic of an Australian top order that had no answer to the Springboks' fast bowlers on hard, bouncy pitches. Of the 80 wickets they lost, 52 were captured by Peter Pollock (Shaun's father), Procter and Barlow, and Procter - he of the floppy, flaxen hair and whirlwind action that was once a tourist attraction in Bristol - accounted for half of those. On the flipside Graham McKenzie, Australia's ace strike bowler of the decade, took 1 for 333 in the series, his solitary success coming in the second innings of the final Test when Bacher was out undefinedhit wicket for 73.

Four Springbok batsmen averaged over 50 and two of them, Pollock and Richards, over 70. Only one of their opponents, Ian Redpath, averaged more than 40.

The Aussies brought with them a mystery spinner called John Gleeson, who was touted as their secret weapon. He could bowl off- or leg-breaks with equal facility without a discernible change in action. This involved flicking the ball from a grip comprising thumb and folded middle finger and such was his value that he insured his right hand for A$10,000.

Gleeson took 18 wickets in two provincial matches at the start of the tour and then five more in the first Test at Cape Town. Most of the Springboks were seeing him for the first time and initially struggled to fathom him. But it was Richards, the most junior of them, who claimed to have worked him out. It was simple, he told his team-mates, if you see one finger and the thumb, it's the offy; if you can see more than one finger over the top, it's the leggy. Was he right? Not once in seven innings did Gleeson, who took 19 wickets in the series, get him out.

The series ended when Bacher took the final catch. It was the South African captain's only series in charge - a 4-0 walloping of Australia - and then it was all over forever.

Rodney Hartman is a cricket writer and former sports editor in Johannesburg. He is also the author of Ali: The Life of Ali Bacher.