Notes by the Editor

Scyld Berry

|

|||

|

Related Links

Cricketers of the year : Graeme Swann

Cricketers of the year : Graham Onions Cricketers of the year : Matt Prior Cricketers of the year : Michael Clarke Essays : Sehwag named Wisden's Leading Cricketer Cricketers of the year : Stuart Broad Other links:

Buy Wisden Almanack 2010

|

|||

An Indian businessman arrived at the India Office in London more than a century ago, seeking permission to start the first steel industry in his own country. Jamshedji Tata was graciously given permission, but only after the Viceroy of India had declared that he would eat his hat if Tata succeeded in producing one ingot of steel. As the Allied war effort in Asia was later to depend on the steel made in the city named after its founder, Jamshedpur, it was just as well for most of us - if not for the viceregal digestion - that Tata did succeed.

Indian businessmen have now taken over the English invention of Twenty20 cricket, just as Jamshedji's descendants, the Tata Steel Group, have bought up what was British Steel. Last year the second Indian Premier League was staged in South Africa, relocated there with a speed and efficiency previously unknown to cricket, and the inaugural Champions League - the first tournament for domestic Twenty20 winners, and some runners-up - was staged in India. While the International Cricket Council repeatedly stated that Test cricket is the highest form of the sport, they organised a second World Twenty20, and seem to be turning it into an almost annual event.

The England and Wales Cricket Board announced before the start of last season that the 2009 Pro40 would be the final 40-over competition, and that it would be replaced by an all-singing and all-dancing Twenty20, so that county cricket would have not one but two 20-over tournaments per summer. Later, the ECB worked out that the sums did not add up, reverted to one 20-over tournament, and abolished the domestic 50-over competition instead. There was no catching the Twenty20 boat once it had sailed east.

England regain the Ashes

Of England captains, only Len Hutton in 1953 and Stanley Jackson in 1905 have done as much as Andrew Strauss accomplished to regain the Ashes during an exhilarating summer: David Gower could be added to this roll of honour, but Australia were at their lowest ebb in 1985. All of these four captains were the leading run-scorers on either side. Their examples created an admirably resilient team spirit among their players. Lower-order batting is one key indicator of a team's morale, and in 2009 England's not only scored more runs, they scored them far more quickly than Australia's. In consequence, England had time to win the two Tests they dominated, whereas Australia had time to win only one.

|

|||

Strauss was lucky again in that the Australians were knocked out of the ICC World Twenty20 by West Indies and Sri Lanka. Two warm-up games in a month did not give their bowlers sufficient opportunity to adjust fully to the Dukes balls, now used in Tests only in England. Even so, Strauss and his team deserve great acclaim, especially as he had been in the job for no more than six months, his counterpart Ricky Ponting for five and a half years.

The natural order over the last century is pretty clear: in Australia, Australia win almost twice as many Tests as England; in England, the sides are well matched; and normally England need a great fast bowler to tip the balance, wherever the series is staged. Strauss had the benefit of two superlative spells of fast bowling, by Andrew Flintoff at Lord's and by Stuart Broad at The Oval. But the most succinct explanation of this conundrum - how on earth did England win when they averaged 34.15 runs per wicket against Australia's 40.64, the biggest disparity that has ever been overturned in any Test series - has to be this: Strauss's batting and captaincy, and the team spirit which he and the new coach Andy Flower created. (If it is thought that I have been swayed by ghosting Strauss's book on the Ashes, I would point out that our reviewer of the series, Christopher Martin-Jenkins, reaches the same conclusion; and Strauss won the Compton-Miller medal as player of the series.)

One particular judgment stands out. Strauss was widely criticised in the media for not making Australia follow on at Lord's, as would have happened in the old days (when there were rest days and no back-to-back Tests). But had Australia batted at anything like their normal rate on that sunny third day at Lord's, against tired bowling, England could easily have been set 200 in the fourth innings, or more. Overall, Strauss was criticised as too defensive, yet his team took six Australian wickets in one session, seven in another, and eight in another. It is worth noting that Hutton, and Peter May in 1956 when he retained the Ashes, were even more criticised by the English media, for being even more defensive.

Same result, much less impact

The 2009 series was the best - the most deliciously fluctuating - Ashes series since 1981, with one exception. But it did not excite the public imagination to anything like the same extent as the one of 2005. Four causes were widely identified. One was that fewer great cricketers were involved in 2009: only one, Ponting, unequivocally deserved this title, although he was not treated as such by the sections of crowds that booed him. Secondly, the suspense was not so intense because England had been waiting only two and a half years to regain the Ashes, not half a generation as in 2005. Thirdly, although there was so very little between the teams, the Tests themselves were not close, except for Edgbaston, and that was ruined by rain.

Fourthly, and perhaps most importantly, the 2009 Ashes series had a television audience of one quarter of what it had been at the equivalent stages in 2005. It was not on free-to-air television - and, a few months afterwards, a committee chaired by David Davies recommended to the UK government that home Ashes series should be available, owing to their "national resonance", for all to see. This has to be right: the creation of role models is essential for the health of English cricket. Sights such as Flintoff's spell on the fifth morning at Lord's, or Broad's at The Oval, or Strauss's sangfroid in both innings on the turning pitch which was conveniently provided for that game, or Graeme Swann's exuberance whether batting or bowling spin, are seeds which have to be sown if the sport is to prosper.

Sophia so good

|

|||

Gibson's greatest challenge

England's good housekeeping in the Ashes, compared to Australia's profligacy with wides and no-balls, is illustrated in our review of the series. Later, in South Africa, they bowled only four no-balls in four Tests: an issue which had bedevilled England had gone away. Ottis Gibson, their bowling coach, can take much of the credit, not for waving a magic wand, but for supervising practice day after day, making sure that England's bowlers always had an umpire standing in the nets, and breaking the bad habit.

If anybody can talk enough sense to bring West Indies' administrators and players together, it will be Gibson in his new role as their head coach. The very existence of the West Indies cricket team - rather than separate entities such as Jamaica or Trinidad & Tobago - will be in doubt if there is another players' strike to follow the one last year, when their first team missed the Champions Trophy and their home series against Bangladesh. As Chris Gayle takes bowling apart, he reminds us that West Indian cricket at its exuberant best has a style like no other.

Where there isn't a will…

If the Football Association reduced the length of Premiership matches to 72 minutes, supporters would naturally claim that the chances of England winning the World Cup had been diminished. If the Rugby Football Union reduced professional club games to 64 minutes, the effect upon the national team would be criticised as injurious. Yet, somehow, the ECB have got away with abolishing the domestic 50-over competition: no limited-overs match henceforth between counties will be longer than 40 overs per side.

"If at first you don't succeed, try, try and try again" is a fine maxim - though not, as the joke goes, for sky-divers. But England's administrators have changed it into: "If at first you don't succeed, give up." The facts are:

| Team | World Cup | Champions Trophy | World T20 | Total |

| Australia | 4 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| West Indies | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| India | 1 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 1/2 |

| Pakistan | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 1/2 | 0 | 1 1/2 |

| New Zealand | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| South Africa | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| England | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

|||

When Lord MacLaurin was chairman of the ECB, their mission statement was for England to be the best in the world: to be No. 1 in Test and one-day cricket. Not any more: this has all been watered down into being "successful". Before we move on, however, we should record that five first-class counties had the interests of the national team at heart and acknowledged the hand which feeds each of them over £2m a year. The other 13 counties ignored the recommendation of the ECB's own cricket committee that 50-over cricket should be preserved, voted for a 40-over competition, and then had their majority verdict endorsed by the full board of the ECB, which is designed to rubber-stamp the first-class counties' interests.

The official rationale was that 40-over cricket was more popular with county members than 50-over cricket. Of course it was: one was played in summer, the other in spring. Snail-racing and toenail-clipping are likely to attract more spectators than a lukewarm 50-over game in April - which is when the Friends Provident Trophy was fated to start - between two counties playing the day after they have finished a four-day match. At the end of last April three counties played a Championship game from Wednesday to Saturday and a 50-over match on Sunday and another 50-over match on Monday, with much travelling in between. When the members of the Professional Cricketers' Association voted last summer, it was not surprising that over 82% expressed the belief that the domestic game should mirror international cricket; and 89% said they did not have faith in the ECB's leadership.

There is nothing wrong with a 50-over match played between two relatively fresh and skilled sides on a true pitch. The essential ingredients are genuine pace, high-class spin, and batsmen trying to bat through an innings to make hundreds. Such was the standard of 40-over county cricket last season that the death bowling for Warwickshire and Worcestershire was done by Jonathan Trott and Daryl Mitchell, bowling gentle medium-pace. No wonder the two counties in the inaugural Champions League were embarrassed, and only one county cricketer (Eoin Morgan) was bought in the IPL auction of 2010. Only two one-day hundreds were scored for England last year; and the habit will be acquired with even greater difficulty in 40-over county cricket, unless the bowling becomes ever more dire. The ICC regulation that a ball must be changed after 34 overs in a one-day international, as it starts to reverse-swing, will be another novelty to which England's future 50-over players will be forced to adjust.

Taylor-made to succeed

Winning World Cups and the World Twenty20 is not something to which England Women are strangers, and they must be congratulated on doing both in the space of a few months. Organising the women's tournament alongside the knockout stages of the men's World Twenty20 last summer was a fine initiative by the ICC; and it allowed television viewers to see the exceptional skill of Claire Taylor. In England's semi-final against Australia at The Oval, Wisden's first female Cricketer of the Year gave a perfect demonstration of run-chasing by scoring 76 not out from 53 balls. The ECB deserve credit, in this case, for giving England's women cricketers exactly what they need to be the best of their kind. Where there is an official will, there is a way to win.

Pandora's abdominal protector

As with every human invention, both good and ill have resulted from India's virtual takeover and vigorous commercialisation of Twenty20 cricket. For good, the parameters of batting and fielding have been extended, increasing the game's delights. Bowling has less improved: at least that seemed to be the case at Centurion last November when England were hit by South Africa's opening pair of Graeme Smith and Loots Bosman for 170 runs. What used to take a couple of sessions in a Test match, or even a whole day in the 1950s, was scored from 13 overs.

|

|||

During the World Twenty20 in England, Sri Lanka's Tillekeratne Dilshan popularised the stroke whereby he went down on his back knee and helped the ball over his left shoulder or straight over his head. Some called it the "Dilscoop", but it would be wrong to credit him with the stroke's invention. In 1933, when batting for the West Indians at Lord's, Learie Constantine scooped over his head for six a full toss from MCC's pace bowler Maurice Allom, and there are earlier references too. Australia's wicketkeeper either side of the First World War, Hanson Carter, who in his day-job was an undertaker, might have got the idea for his shovel shot from grave-digging. After the introduction of the helmet, the stroke became less fraught with physical danger and was occasionally used.

Let Dilshan be truly honoured for his bravery during the terrorist attack on the Sri Lankan team bus in Lahore, when a cricket team was directly targeted for the first time, and the sport became no longer an escape from daily life but part of it. Dilshan's heroic role in piloting the team bus to safety is described in the article following these Notes.

Another good to come out of Twenty20 is that the boundaries of fielding have been extended, literally. Several international fielders have now palmed the ball up inside the rope to stop it going for six, been carried over the boundary by their momentum, then returned to the field of play to complete the catch. As described in our introduction to the Laws (page 1499), MCC now intend to amend one of them, without spoiling either the fun or the breathtakingly gymnastic skills Twenty20 has mothered. The change is designed to stop a fielder back-pedalling beyond the boundary before leaping into the air and palming the ball back inside the rope.

Where there's an ill…

It was neither good nor ill, merely silly of the IPL's commissioner, Lalit Modi, to claim: "The quality of cricket that is played in the IPL is by far the best in the cricket matches that I have seen or for that matter anybody else has seen." One expects a businessman to talk up the value of his product, especially during a global recession. Far more disturbing was the Indian board's reprimand of their highly estimable coach, Gary Kirsten, for making perfectly valid criticisms of the IPL. Almost half of each franchise team consists of uncapped young Indian players, which is a commendable initiative, and it is obvious that the standard of the IPL is below that of international cricket.

For staging the second IPL in South Africa without any surveillance by the Anti-Corruption and Security Unit, "cricket paid a price", according to the ICC. Shortly afterwards "a number of approaches" were made to various cricketers to fix matches in the World Twenty20 in England. It is a matter of faith whether we believe the ACSU's claim that all of the approaches made to players were reported to them. The growth of Twenty20 has attracted many people not interested in the traditional formats and, in these straitened times, not all will have the good of the game at heart. Tim May, chief executive of the international players' union FICA, said: "Twenty20 is just ripe for corruption - the shorter the game, the more influence each particular incident can have. So I think it opens up a great deal of opportunities for the bookmakers to try and corrupt players." And a corrupt cricketer will take the contagion back to the country from which he comes.

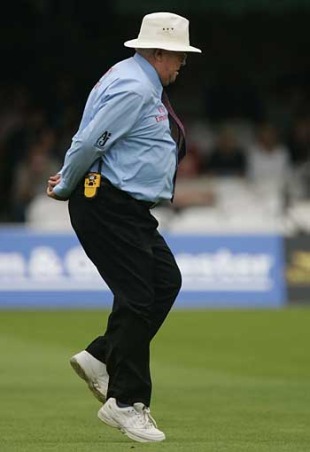

Umpiring after Shep

|

|||

Four Test series trialled referrals, an immensely complicated system whereby a team could refer a decision by the two on-field umpires to the third umpire, with a maximum of three unsuccessful referrals per innings. Then came the Umpire Decision Review System, with a limit of two unsuccessful reviews per innings. This was an improvement, if only because anything had to be better than its predecessor, but it was still the source of conflict - notably when Graeme Smith was given not out in the Johannesburg Test against England. And, while players openly questioned the umpires' decisions, spectators in the ground had to twiddle their thumbs, not having the faintest idea what was going on.

Fashions change. It has become polite to turn your back on a person, if he or she is entering a PIN number. It is now considered sensible to dispense with a third man, however many edges fly for four: it is no coincidence that last year saw the second-fastest rate of scoring ever known in Test cricket. But questioning the umpire's decision must never become a fashion: it will have damaging long-term consequences for all levels of the game. What may start as fun - a club bowler or fielder making the shape of a T when he disagrees with a decision - will become a whole process of insidious undermining.

I remain with the ex-Sir Allen Stanford on this one, although not, I trust, in other respects. The system of consultation that he trialled in his Twenty20 matches in Antigua is the best seen so far. Technology needs to be incorporated on an increasing scale: if the best three or four umpires, such as Simon Taufel and Aleem Dar, officiated in all Test matches, I think everyone would be happy simply to have line-decisions settled by technology, and for the rest accept umpires' very occasional human errors. But the standard dips alarmingly after this elite handful, so technology such as Hawk-Eye, Hot Spot, and the Snickometer, must be used at the highest level.

It would be best if the three umpires arrived at a decision together, through consultation, as in the Stanford tournament, and without any questioning by the players. There is enough on a captain's plate already without the decision of whether or not to use a review becoming a major, match-turning issue. It is also illogical that justice should be rationed: after two unsuccessful reviews, a team can suffer a gross miscarriage without any recourse.

And maybe the three umpires should take it in turns, so that each does one session per day in front of the television and two in the middle. But let the ICC do their experiments outside Test series. The last year of umpiring trials - while earnest and well-intentioned - damaged the image of the game, and of the ICC itself, because any organisation which keeps on tinkering and making new announcements loses respect.

Value for money

Lest it be thought I have been too critical in these pages of the ECB, let me bring the reader's attention to the good which they do. They have spread out an umbrella under which staff and many, many volunteers do invaluable work for club or school cricket. In addition to promoting women's cricket in the way it should be, during 2009 the ECB have:

- donated £2m to Chance to Shine

- made grants (so much more useful than loans) of over £2m to recreational clubs

- donated £400,000 to Lord's Taverners

- given more than £3m to the 38 county boards to spend on their development operations

- spent another £3m on development managers and officers, and on age-group and Minor Counties cricket

- spent over £800,000 on subsidising and administering coaching programmes for everyone below elite Level 4

- had to cough up £650,000 a year on child protection, in the form of Criminal Records Bureau checks. (Ludicrously, the government insist that even a regular club scorer now has to have a CRB check. A child cannot go into the scorer's box and ask for his or her stats without this bureaucracy.)

Personally, I would like to see a little less of the development budget going on coaching and a little more on providing basic playing facilities. While covering England's one-day series in South Africa, I visited the Galashwe township in Kimberley, where Loots Bosman grew up and learned his cricket at a club called Yorkshire, and another township club in Port Elizabeth, called Gelvandale, again with very few resources, which has produced three Test players in Ashwell Prince, Alviro Petersen and Wayne Parnell. What children need if they are to play cricket are sunshine, space, a true surface of some kind (it doesn't have to be turf initially: Prince and Petersen grew up playing for one street against another), and a bat and a taped tennis ball. These are inexpensive items, if not always easy to obtain. Coaching comes later; and role models are necessary too. Bosman, I should add, is still the only indigenous African batsman to have represented South Africa.

Add up all the ECB's sums and you can just about allow their claim that they invest 20% of their total cricket expenditure on development. What should be debated is how the rest of their net income - mostly generated by the England team through broadcasting deals - is spent. Well over half of it goes in distribution fees to the counties, only for them to do what is sometimes not in the national interest. If the first-class counties accept over £2m a year each, as they do, they should feel obliged in return to raise standards by reducing the amount they play and to mirror international formats.

Less stress for Strauss

It is nothing less than outrageous that the England team is flogged into the ground primarily to subsidise the counties. One by one, the England players last year - after climbing the summit of their Test match profession by defeating Australia - fell off their perches. In the one-day series alone, James Anderson, Stuart Broad and Paul Collingwood, three of the pillars of England's one-day side, had to be rested; and Anderson picked up a knee injury that dogged him the whole winter. It was indefensible to schedule a flight to Belfast the day after the Ashes, and for England to be forced to play ten limited-overs games in the four following weeks, then stuck on the plane next day for the Champions Trophy.

Restraint, not rotation, is the answer. It was fine to rest Anderson for England's tour of Bangladesh, and consistent with English cricket's tradition of allowing fast bowlers to miss a tour. Otherwise, the 11 best cricketers must take the field, in a mentally and physically fit state. (It is surely no coincidence that Australia have fallen from grace at the same time that their programme has been increased almost to England proportions.) To field an England side packed with replacements, because the main players are exhausted, would be to defraud spectators, viewers, broadcasters, and the game itself.

It was an eloquent condemnation of the ECB's scheduling, and their failure to implement a key recommendation of the 2007 Schofield Report which they themselves commissioned, when Strauss felt unable to lead England on their tour of Bangladesh. All England's modern captains have been stressed out by the job, but it happened to Strauss after a single year. He and Andy Flower had rapidly become as fine a pairing as Michael Vaughan or Nasser Hussain with Duncan Fletcher. Strauss had led England to the Ashes, and a shared Test series in South Africa, and had regenerated their 50-over side. When England played without him, they lost a 20-over game against the Netherlands at Lord's. Strauss and his players deserve better treatment from their employers.

Test of champions

Calls for a Test championship play-off have grown louder, but a fair and workable plan has yet to be proposed. If every one, two or four years, the top two countries meet in a one-off final, far too much weight could fall on the toss. The best team can be decided only by a full Test series. This is why they were invented.

|

|||

Until a workable way is devised, it is up to administrators to organise the Test programme far more coherently - if they truly want the format to survive. India played South Africa, in India, in a three-Test series in 2008 and again in a two-Test series less than two years later in early 2010. This is lamentable: far better to stage one series of five Tests, identify the stronger side in all conditions and, over two months, engage the attention of the whole cricket world. Instead, India and South Africa decided the top place in the world Test rankings - in India's favour - on the inadequate basis of two games.

This summer will offer a taste of what a Test championship play-off would be like, when Pakistan meet Australia at Lord's and Headingley: the first neutral Tests in England since 1912, when Australia met South Africa in a triangular series. One hopes the weather is kinder than it was then. The ECB are right to help Pakistan's national cricket team survive in exile, but the world should provide for Pakistan's future at the same time. As land prices are not at their most expensive, perhaps now is the time to buy an out-of-town venue which can be built like a fortress for security - much like Mohali, on the outskirts of Chandigarh, where England played in December 2008.

If the ICC move to India, we might as well say ta, ta

The ICC are set to move their headquarters from Dubai. If they relocate to India, cricket will be compromised. Were the ICC to be based in New Delhi or Mumbai, the power-base of their next president Sharad Pawar, the staff would become predominantly Indian as the main current administrators would find it too difficult to relocate their families there, and the organisation would cease to reflect the attitudes and values of all its members. The sport would become as much of a hostage to India and their ambitions as it was to England and Australia when the headquarters were at Lord's. Cricket, like any other organism, needs diversity to evolve, rather than Indianisation. It is not a business, or an industry like steel, to be taken over.

Buy the 2010 Wisden Cricketers' Almanack