Whose line is it anyway?

Leg-theory in Adelaide almost triggered a riot seventy-three years ago

Gideon Haigh

25-Feb-2013

ESPNcricinfo Ltd

Leg-theory in Adelaide almost triggered a riot seventy-three years ago. Today it brought a Test match almost to a standstill. You’d have gotten tasty odds before this game on the likelihood of the first English double hundred since Walter Hammond, or of England setting a new Ashes partnership record at this ground. But not perhaps as enticing as those on Shane Warne auditioning for the role of Australian wheelie-bin, with over upon over outside leg stump, not in search of rough, but of respite.

On the day that 'The Australian's trenchant Malcolm Conn announced that England had ‘unveiled its latest secret weapon to retain the Ashes – boredom’, Australia demonstrated that it is a game two can play. It is fair to say that England had the better of the détente that ensued. It isn't unfair to say that, although a draw looms as the likeliest outcome, and Australia has the batting to kill the game off, only one side can win this game: odds on that team being England would only two days ago have been astronomical.

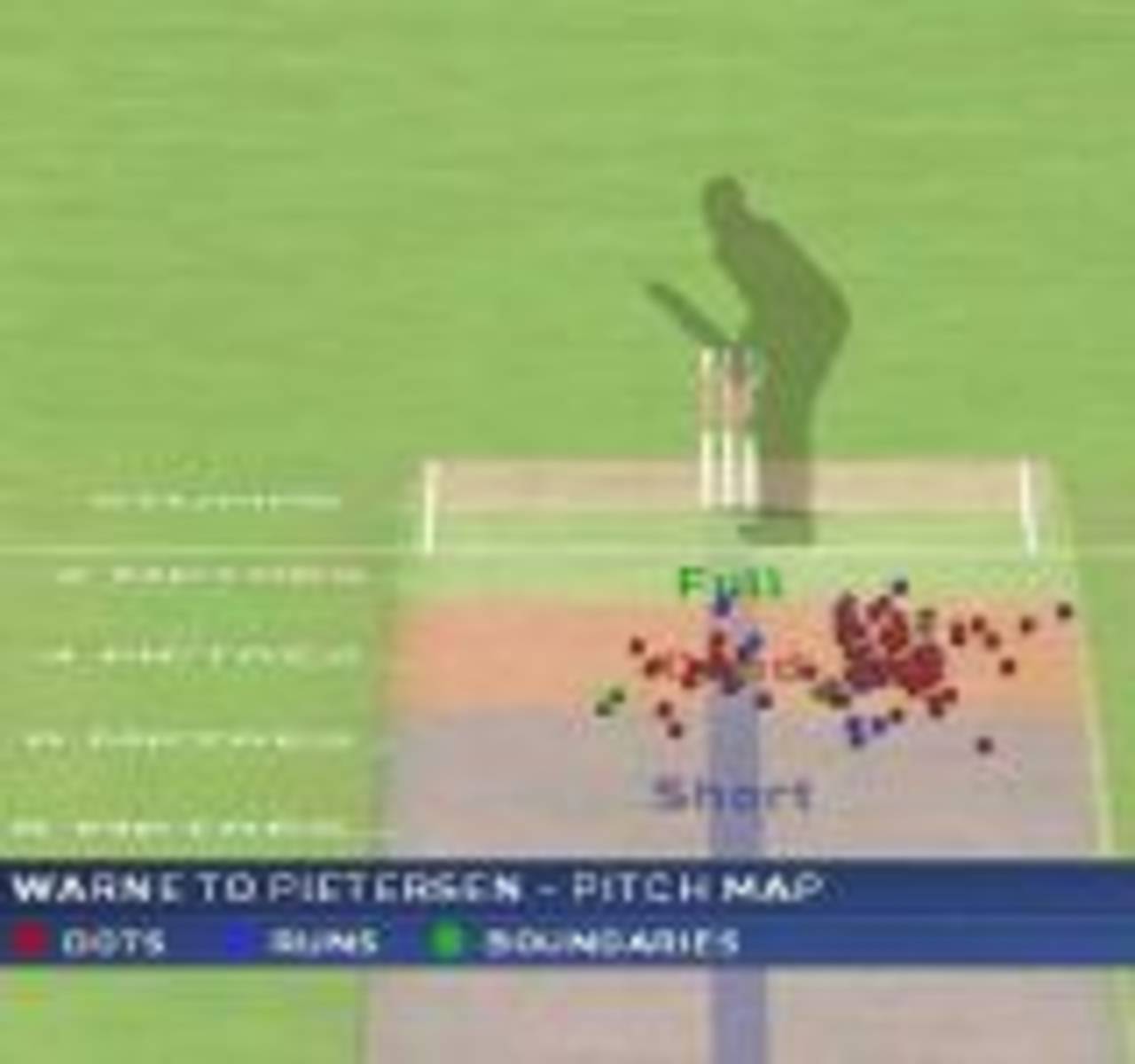

Kevin Pietersen, moreover, has rather transfixed the Australians. It is remarkable how he seems to depopulate a field. Warne confronted him first with two on the fence, behind square leg and at mid-wicket, an exceptionally fine leg, a short mid wicket and a mid on. There was an extra cover sweeper, who was essentially a wasted man, and a mid-off three quarters of the way to the fence, not much more active. It was a plan, of sorts – but not much of one. Pietersen promptly foiled it by finding space between the bowler and mid on, then between the mid-on and short mid-wicket – majestic shots taking him to the brink of his hundred. Warne looked again as he did on Friday, that he would be happy to call it a draw, and settle for a round of golf.

The Australian default setting in such circumstances is usually to stockpile maidens. But from Warne, the leg spinner who has reinvented bowling from round the wicket as an attacking option, the psychological concession of yielding two feet outside leg stump was considerable – like an agreement to drive at 40kmh in a 100kmh zone. It wasn’t a popular strategy: Warne provoked his biggest cheer during the day when he was called for a wide for Rudi Koertzen. Nor was it as economical as Warne would have wished; he was relieved in the afternoon after a spell of 15 wicketless overs for 44. And like many an anti-social activity, it set a bad example on the impressionable young, for Michael Clarke bowled his left-arm darts from over the wicket to no conceivable end.

It was hard not to notice, too, how much more effective Warne was when he resumed bowling over the wicket after Pietersen’s dismissal, having Geraint Jones caught from a casual stroke, and again beating the outside edge. England’s batting in the Ashes of 2005 seemed to involve two different games: one when Warne was involved, one of somewhat lower intensity when he was not. In the Ashes of 2006-7, Pietersen looms as that defining figure. Has there been a taller batsman with daintier footwork? It is almost a rule of cricket that physical size and footwork are in inverse relation, Clive Lloyd and Graeme Pollock being the paradigmatic examples of the big and the still - a tall or heavy man with a long reach, of course, can achieve leverage by a tilt of the body and shift in his weight. But Pietersen’s feet are always going somewhere, usually into harm’s way, and always with positive intent.

Collingwood does his work less obtrusively. Pietersen wants to find out about his game; Collingwood already knows it, back-to-front and inside-out. His 206 was a painstaking innings but never a laboured one. He is a busy cricketer, ticking over like a cab sitting on a rank, eager for fares, ready to zoom off. He is also a valued teammate, to judge from the winding gusto with which Pietersen hugged him as his landmarks were attained.

The Australian attack was willing enough. Lee’s second over of the day was his best of the series, a catalogue of his capabilities, including a rasping riser, a withering yorker and a caught behind appeal of impressive unanimity, with only Bucknor demurring. Correctly, it would seem: sent down to forensics by Channel Nine, the evidence came back without bloodstains or power burns. Even Lee was steadily neutered by the surface. In his 30th over, his fastest bouncer was dashed against the square leg fence by Pietersen, and his slower ball sent skimming through cover by Collingwood. But he did have the energy to offer his hand when Collingwood passed his double hundred, for which he’ll probably get a ticking off from Dennis Lillee.

Stuart Clark has a smidgeon of the stocking-masked hoodlum about him, with his broad nose and close cropped hair, and he took his cosh to Collingwood in a spell of persistent but shrewd short-pitched bowling from the Cathedral End, with a catcher in place at a fine leg gully. Both men had their dander up: Collingwood bided his time, finally found a ball on the line to pull, then blasted the overpitched sequel through covers for four. Again, though, Clark was the pick of the bowlers, finally seeing Collingwood off with a nifty leg cutter, and sparing McGrath a lot of the donkey work that in days gone by would almost certainly have been his. There is a school of thought that the presence of the thrifty will extend McGrath’s career. Mind you, if it means he has to bowl on more pitches like this one, McGrath might not welcome that opportunity.

Gideon Haigh is a cricket historian and writer