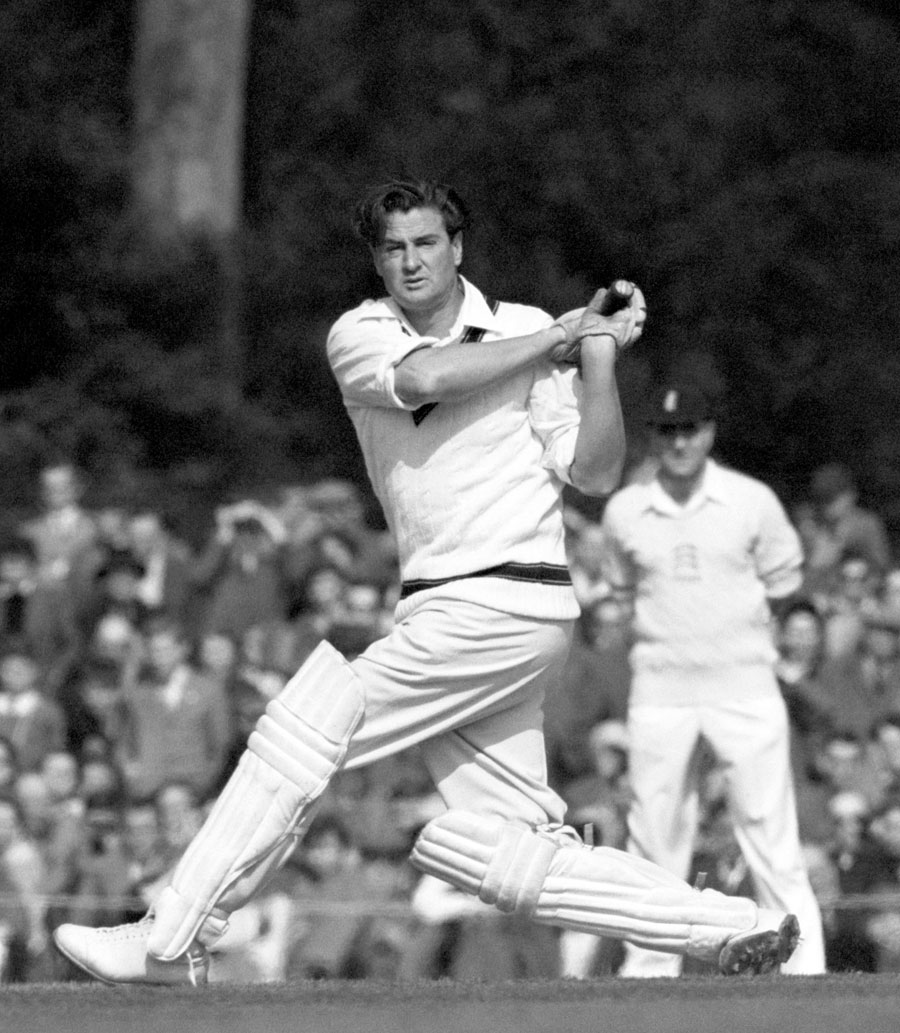

The golden 'Nugget'

Keith Miller had the golden touch whether hitting sixes into the stands, bowling unplayable offerings or thrilling people with his pastime

Peter English

02-Mar-2007

|

|

|

After Don Bradman came Keith Miller. One wowed with his numbers, the other mesmerised with his heroics. For generations of followers Miller had everything: he was a lightning opening bowler; a clever change option; a top-order batsman with a free-spirited method; a successful fighter pilot; a darling with the ladies who was idolised by men; he was comfortable in a dinner suit with royals or a beer at the local pub; had film-star good looks; and was a genuinely good bloke. Not even a Warne-esque list of peccadilloes could diminish his popularity and the overall scope makes him the world's greatest allrounder. No other player has been able to command such respect from so many spheres.

As a multi-dimensional player he was romantically perfect, although his batting average of 36.97 was a little light for the sticklers. Carefree and desperate for adventure, his senses were often subdued when a contest was lulling. In 1948 at Essex the Australians were on the way to scoring 721 in a day when Miller walked out, let himself be bowled and exited for the races. In the crucial moments Miller would be on full alert, but if he failed it didn't really matter. He still had his life, unlike many of those he fought with in World War II. Combat may have stolen his early years and delayed his Test entry, but it helped shape him. Pressure for Miller was the threat of an armed aeroplane. After that everything was a game. Cricket was Bradman's full focus; it was fun for Miller.

Achievements

Miller was the ideal player to help lift Australia out of the post-war gloom. A batsman when he entered the armed forces, he left them as the country's fastest bowler and made his debut in New Zealand in 1945-46. In his next game, against England at the Gabba, he roared with 79 at No. 5 and a match haul of 9 for 77 to show he was capable of performing both disciplines. The first of seven hundreds arrived in the fourth match of the series - the high of 147 came in the run demolition of West Indies in 1954-55 after taking 6 for 107 - and he went to England in 1948 as a key member of the Invincibles.

|

|

|

After spending time in England during the war he felt at home there and was lauded as a celebrity second to Bradman. He managed a Lord's century on the 1953 tour and farewelled the country as a Test player in 1956 with 21 victims, including his only ten-wicket haul, which also came at the home of cricket. Despite a record of 2958 runs and 170 dismissals at 22.97 he was never deemed suitable by the conservative Australian Cricket Board to guide the team. Richie Benaud said he was "the best captain never to lead Australia".

What made him special

Refusing Bradman's command to bowl short at the England No. 3 Bill Edrich at the Gabba in 1946-47 is high on the list. "I'd just fought a war with this bloke," he said. "I wasn't going to take his head off." He also turned up minutes before a state game after the birth of a son to take 7 for 12 - "He was a freak," Alan Davidson said. In England he arrived late to a tour game against Hampshire with more than half the team following a Friday night out in London and shortly after stumps left for a dinner engagement with Princess Margaret.

Refusing Bradman's command to bowl short at the England No. 3 Bill Edrich at the Gabba in 1946-47 is high on the list. "I'd just fought a war with this bloke," he said. "I wasn't going to take his head off." He also turned up minutes before a state game after the birth of a son to take 7 for 12 - "He was a freak," Alan Davidson said. In England he arrived late to a tour game against Hampshire with more than half the team following a Friday night out in London and shortly after stumps left for a dinner engagement with Princess Margaret.

As a pilot he supposedly diverted a flying mission over Bonn so he could see where Beethoven was born and survived crash landings. The only player to appear on the Lord's honour boards for batting and bowling, his photo was one of two in the Canberra office of the Australian prime minister Sir Robert Menzies and his portrait hangs in MCC's Long Room.

Finest hour

Miller's first Test against New Zealand was not recognised until 1948, so when he lined up against England at the Gabba in 1946-47 he felt he was making his debut. In a match that is forever linked with Miller, he refused to bowl short at Edrich, slowed his pace to bowl off-cutters and captured career-best figures of 7 for 60. By then he was 27 and R.S. Whitington, the journalist, cricketer and Miller's friend, believed the allrounder's best batting had already occurred. "It is a tragedy that Australians have never quite seen the Miller of 1945," Whitington said. Miller had scored two centuries at Lord's for the Australian Services XI, but his third in the summer of 1945 was the highlight. Appearing for the Dominions against England, Miller raised a brilliant 185 and launched seven sixes, including one that hit the top tier of the pavilion and another that struck the commentary box. It was the best batting Pelham Warner saw.

Miller's first Test against New Zealand was not recognised until 1948, so when he lined up against England at the Gabba in 1946-47 he felt he was making his debut. In a match that is forever linked with Miller, he refused to bowl short at Edrich, slowed his pace to bowl off-cutters and captured career-best figures of 7 for 60. By then he was 27 and R.S. Whitington, the journalist, cricketer and Miller's friend, believed the allrounder's best batting had already occurred. "It is a tragedy that Australians have never quite seen the Miller of 1945," Whitington said. Miller had scored two centuries at Lord's for the Australian Services XI, but his third in the summer of 1945 was the highlight. Appearing for the Dominions against England, Miller raised a brilliant 185 and launched seven sixes, including one that hit the top tier of the pavilion and another that struck the commentary box. It was the best batting Pelham Warner saw.

|

|

|

Achilles heel

Fun and mischief led to an upsetting of authority that would curtail his leadership ambitions, if not his after-hours activities. Trips to the races were as frequent as photos in the social pages and if he was a modern-day player his lack of focus would have been analysed in detail. During his fighter-pilot days, when living longer than three weeks was an achievement, Miller crash-landed but walked away with the line: "Nearly stumps drawn that time, gents." A bad back lingered from the accidents and would hamper his reluctant but brilliant bowling throughout his career.

Fun and mischief led to an upsetting of authority that would curtail his leadership ambitions, if not his after-hours activities. Trips to the races were as frequent as photos in the social pages and if he was a modern-day player his lack of focus would have been analysed in detail. During his fighter-pilot days, when living longer than three weeks was an achievement, Miller crash-landed but walked away with the line: "Nearly stumps drawn that time, gents." A bad back lingered from the accidents and would hamper his reluctant but brilliant bowling throughout his career.

How history views him

An Invincible whose name is immortalised. He died in 2004 aged 84 and Australia remembered a national hero. Those who watched him never forgot it, those who didn't always regret it. Nicknamed 'Nugget', he had the golden touch whether hitting sixes into the stands, bowling unplayable offerings or thrilling people with his pastime. Thousands lined up at his state funeral and an Englishman who had never met Miller but wanted to pay his respects joined jockeys, cleaners and officials to say goodbye to a man Benaud said had "more charisma than any other cricketer or sportsman I've seen".

An Invincible whose name is immortalised. He died in 2004 aged 84 and Australia remembered a national hero. Those who watched him never forgot it, those who didn't always regret it. Nicknamed 'Nugget', he had the golden touch whether hitting sixes into the stands, bowling unplayable offerings or thrilling people with his pastime. Thousands lined up at his state funeral and an Englishman who had never met Miller but wanted to pay his respects joined jockeys, cleaners and officials to say goodbye to a man Benaud said had "more charisma than any other cricketer or sportsman I've seen".

Life after cricket

For a while he was a cordial and liquor salesman, but he spent a lot of time as a touring journalist and columnist for English and Australian papers. Writing for his editors, Miller told the players not to take any notice of what was printed under his name. Trips to England were high priorities for cricket and social occasions, but in his latter years watching the game became less attractive with the crowded program. He had reclusive tendencies and hip surgery, cancer and a stroke also slowed him down. In February 2004 he attended the unveiling of his statue at the MCG, but it was his final public appearance.

For a while he was a cordial and liquor salesman, but he spent a lot of time as a touring journalist and columnist for English and Australian papers. Writing for his editors, Miller told the players not to take any notice of what was printed under his name. Trips to England were high priorities for cricket and social occasions, but in his latter years watching the game became less attractive with the crowded program. He had reclusive tendencies and hip surgery, cancer and a stroke also slowed him down. In February 2004 he attended the unveiling of his statue at the MCG, but it was his final public appearance.

Peter English is the Australasian editor of Cricinfo