Sobers's Rhodesian misjudgment

Martin Williamson on Garry Sobers's big mistake when he played cricket in Rhodesia

Martin Williamson

04-Feb-2006

|

|

|

In 1970 Sobers played for the Rest of the World side in England in a five-match series which replaced the abandoned tour by South Africa. Towards the end of the summer, Eddie Barlow, who was also in the Rest of the World XI, suggested to Sobers that he might like to take part in a double-wicket competition in Salisbury (now Harare). Sobers thought it over, and having been assured that there was no apartheid and no racial discrimination in team selection, he agreed to go. "Had I known the furore my visit was to cause," he recalled, "I would not have gone." The story broke on September 7 when a London newspaper reported his proposed visit and the condemnation was immediate.

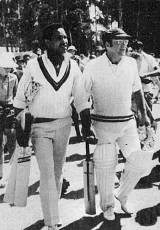

Sobers arrived in Salisbury early on September 12, the day of the event, and after a few hours' rest he travelled to the ground where he partnered Ali Bacher in the double-wicket competition. "We failed to win," Sobers admitted. "It wasn't surprising since I stepped straight off the aircraft."

He did, however, receive a rapturous reception from the capacity house, and a standing ovation all the way to the middle accompanied by a rendition of "For he's a jolly good fellow". For his day's work, Sobers was paid £600.

That night, Sobers had dinner with Ian Smith, the Rhodesian prime minister, who he said was "a tremendous man to talk to". In all, Sobers was in Rhodesia for less than 48 hours, but he only became aware of the real effect of his trip when he returned to Barbados.

He was greeted by a media scrum, and that was followed by condemnation in the press. The Workers Voice in Antigua labelled Sobers "a white black man", while many others demanded he be stripped of the West Indies captaincy. If he hoped the furore would die down, he was to be disappointed.

Things reached a head on October 10 when Forbes Burnham, Guyana's Marxist prime minister, announced Sobers would not be welcome in his country unless he apologised. Given that West Indies played at least one Test each year at Georgetown, that posed major problems. It was not inconceivable that the West Indies board would cancel the Guyana Test, and that could have led to Burnham insisting that the Guyanese players in the side - including Rohan Kanhai and Clive Lloyd - boycott the team. And the board was also concerned that were it to sack Sobers, then Barbados could withdraw in protest.

On October 14, the Jamaican Labour Party called for his resignation. There was support, especially from his homeland, and Vernon Jamadar, Trinidad's leader of the opposition, praised Sobers's "calm dignity in response to the primitive savagery of West Indian gutter politicians".

But then the international ramifications became clearer when Sobers was warned that Indira Gandhi, India's prime minister, had indicated that a West Indian side including Sobers might lead to the cancellation of the 1970-71 tour by India. The pressure on him to apologise was considerable and the row would not go away. Eric Williams, Trinidad's prime minister, drafted a letter to the West Indies board for Sobers to sign, and Wes Hall, a long-standing friend of Sobers, flew from England, where he was coaching, to deliver it to him.

|

|

|

But why had he gone in the first place at a time that South Africa, Rhodesia's neighbour, was being roundly and almost universally shunned? Michael Manley, the Jamaican prime minister who wrote A History of West Indies Cricket described Sobers as "politically unconscious". He continued: "To say there was an uproar in the Caribbean is comprehensively to understate what took place. Caribbean political leadership in government, in opposition, and of course in the lunatic fringe, found one voice in which to denounce Sobers for going to Ian Smith's rebel, racist nation. When Sobers became aware of the reaction to his visit he was aghast. It had simply not occurred to him that he had done something wrong."

Manley also gave an opinion as to why Sobers was so readily forgiven for something that labelled many cricketers in the future as virtual pariahs in Asia and the Carribean. "A grateful Caribbean grabbed the apology with both hands," he wrote. "He was, after all, the first complete Caribbean folk hero, after George Headley. The thought that he might be lost as a consequence of a political gaffe was intolerable. For the great majority, the incident was forgiven and promptly forgotten."

Is there an incident from the past you would like to know more about? E-mail us with your comments and suggestions.

Bibliography

Wisden Cricket Monthly - Various

The Cricketer - Various

Playfair Cricket Monthly Various

A History of West Indies Cricket - Michael Manley (Andre Deutsch Ltd 1988)

My Autobiography - Garry Sobers (Headline, 2002)

Wisden Cricket Monthly - Various

The Cricketer - Various

Playfair Cricket Monthly Various

A History of West Indies Cricket - Michael Manley (Andre Deutsch Ltd 1988)

My Autobiography - Garry Sobers (Headline, 2002)

Martin Williamson is managing editor of Cricinfo.