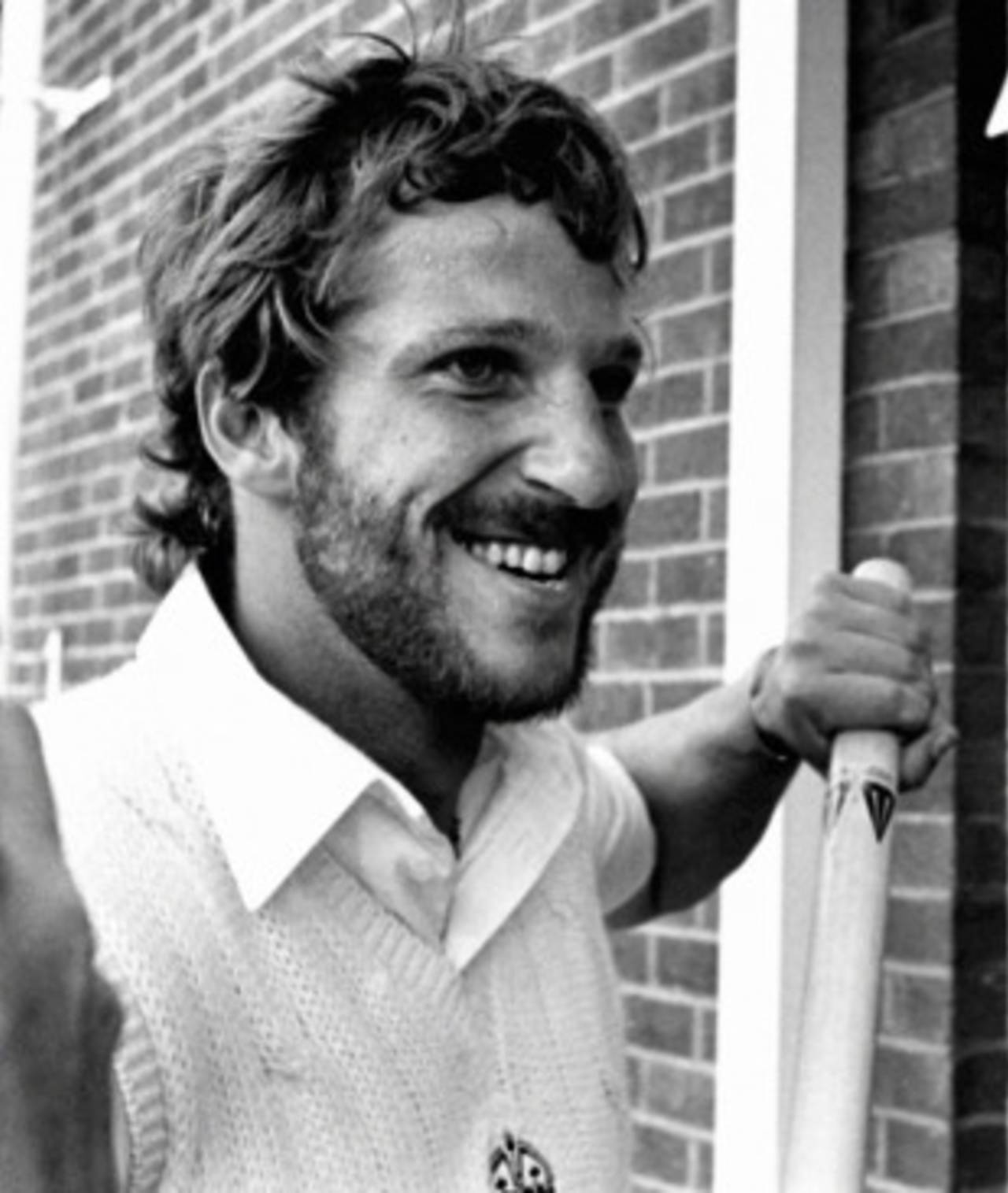

Herein lies a cricket tale of a heady concoction of exceptional talent laced with self-belief to match. Such gargantuan self-belief, in fact, that just as the Piraha tribe of northwest Brazil speak an obscure language in which there is no concept of numbers, so in the lexicon of

Ian Botham's cricket existence, there is no word for "impossible". He does not, and never has done, "can't". In the 15 years that he played international cricket, there was no batsman alive (or indeed, dead) who could not have been dismissed by a bouncer (this despite being, in his lithe, uninhibited pomp, before he lost his waistline and his back went, the finest swing bowler of his or perhaps any generation); no bowler who could not have been bludgeoned into submission; no slip catch that could not have been taken by the expedience of standing two yards closer than anyone else dared; and no situation so dire that it could not have been rescued by his personal intervention.

His extremes, on and off the field, some of them destructive, were indicative of a strength too, a double-O cricketer with licence to thrill and a constitution that would make tungsten seem like talc. Nothing was to be done, or indeed worth doing, if not to excess: the finest all-round performance in Test history came on the back of a 48-hour bender that would have felled an elephant. If, overall, other allrounders of the modern era have come to be regarded as his equal if not his superior - Jacques Kallis, Imran Khan and Kapil Dev prominent, along with Richard Hadlee and, to an extent, Wasim Akram - then none could match the depth and breadth of his deeds in the first five years or so following his dramatic

Trent Bridge debut, when the world was at his feet and the game came so easily to him.

But first, a short but true illustrative anecdote. Botham is playing golf in Australia, and has a short-iron approach shot into an elevated green, while his playing partners watch from above, with a sight of the green that is denied him. He plays his stroke, the ball just clears a bunker, pitches on the fringe and just hobbles onto the putting surface, 30 feet from the pin. Botham stomps onto the green, prowls around for an old pitch-mark - any pitch-mark - close to the hole and makes great play of repairing an imaginary indentation "Spun back," he harrumphed. "Too much action on it." Now the point is not that this was some banal act of bravado or bullshit, but that he really did actually believe that this is what had happened. So secure in his mind was the infallibility of whatever he was trying to do that there could be no other credible explanation. How else could it have got there?

Whether batting, bowling, catching swallows, quaffing bottle after bottle of fine wine, or walking his thousands of miles for charity, his belief (as distinct from self-confidence) in his indestructability was, and remains, quite staggering. He is the best broadcaster in the business: just ask him.

No one has ever been able to turn round a series or his own form quite as dramatically as he, when in 1981, with Mike Brearley's assistance, he pulled himself up from the ignominy of the Long Room's roaring silence after completing a pair against Australia, and from the subsequent loss of the coveted England captaincy after 12 inglorious matches in charge (nine of them, unfortunately against the great West Indies team), to his great feats, shackles removed, at

Headingley,

Old Trafford and

Edgbaston, which are now part of English cricket folklore. Friend or foe, he never did things by halves.

It was the very nature of his all-round skills and temperament that made him the player he was: bowling gave him the licence to bat without inhibition, in the knowledge that redemption could always come with the ball. Likewise, adventurous bowling could be offset with the bat

It is the benchmark of the genuine allrounder that the bowling average should be less than that for batting, and in that regard Botham fits the bill:

5200 runs at around 33;

383 wickets at 28.4. There were 14 Test centuries and 27 five-wicket hauls. He took 120 catches, an England record he holds jointly with Colin Cowdrey, and missed only a handful. He managed to score a century and take five wickets in an innings in the same match on five occasions: no one else has managed more than twice. He was the first to score a century and take 10 wickets in a match, something only Imran has succeeded in matching since. Statistics and bikinis, though: revealing and concealing at the same time.

If he retired a brilliant achiever, then Botham in his youthful prime was a phenomenon. He made his debut, against Australia, in 1977, when he was still 21, and was still only 23 when he completed the double of 100 wickets and 1000 runs, with four hundreds and no fewer than 10 five-wicket innings, in fewer matches, 21, than anyone (Kapil 25, Imran 30). Three years on, just days past his 26th birthday, he reached the next level of 200 wickets and 2000 runs (a further four centuries and eight more five-fors); fewest matches again, 42 (Kapil and Imran both 50). Twenty-eight and it was 300 wickets, and to be precise, 4153 runs; fewest games, 72, once more (Kapil 83, Imran 75). His bowling average for the

first 100 wickets was 18.97; for

200 it was 21.2: if he had retired then, it would have been preserved as amongst the best in history.

But what sort of a cricketer was he? His character was evident from the moment, as a teenager, he picked himself up, having been felled by an Andy Roberts bouncer, spat out his broken teeth, and won a game for Somerset. By the time he made the England side, his reputation was burgeoning, his exuberance there for all to see. His bowling was waspish, the ball snaking this way and that at his command. Batsmen were seduced, slips permanently interested.

At Lord's in 1978, having made a century, he destroyed Pakistan with 8 for 34 - arguably the best display of swing bowling seen in England. Utterly compelling.

Later, as his flexibility decreased and his back got worse, he resorted to bullish bowling, a rampager in a china shop, who as much through force of personality could will wickets from nothing. He had no right to bowl England to victory

at Edgbaston in 1981, but from nowhere he muscled his way to a 28-ball spell of 5 for 1 and beat his chest in animalistic celebration. Even by the end of his career, reduced to military medium (his "Tom Cartwrights", as he called his bowling, not disparaging but honouring his great mentor) he could still con his way to wickets on reputation alone: 4 for 31 against Australia

in Sydney in the 1992 World Cup was a steal, a heist, a hoot. There is, he would observe, a sucker born every minute.

He was a technically gifted batsman too, attacking by instinct but orthodox and defensively sound, so that, out of character, he was able, with massive self-denial, to take almost four and a quarter hours over scoring 51 not out, to save, rather than win, the

1984 Oval Test against Pakistan. Only three times, and each one a century, one a double, had he batted longer, and then at most by an hour. It was incidentally his last Test half-century. As a contrast, his twin 1981 epics, 149 not out

at Headingley and 118

at Old Trafford, came from 148 balls and 103 balls respectively. The bats that he used, unlike those of today, were as heavy as they looked, and his muscularity allowed him to achieve enormous power from the leverage of his arms and legs. He hit beautifully straight. There is no question that with a different mindset he would have made a fine international batsman alone. But it was the very nature of his all-round skills and temperament that made him the player he was: bowling gave him the licence to bat without inhibition, in the knowledge that redemption could always come with the ball. Likewise, adventurous bowling could be offset with the bat. Such freedom of expression, and the confidence to understand its application, is a rarity.

His 1981 achievements define him still, and rightly so given the circumstances. Yet no single match encapsulates more about Botham as a cricketer and person than does the Jubilee Test, played

at the Wankhede Stadium in Bombay in February of the previous year.

Botham was approaching the pinnacle of his all-round powers, the leading wicket-taker (including a remarkable

11 for 186 from 80.5 overs in the first Test) and run-maker in a disastrous three-match series for England in Australia. The team were on the way home when they landed in India, exhausted after an intensive winter. Botham, so legend has it, was demob-happy and had been for several days. From this unpromising base came bowling figures of 6 for 58 in the first innings (five of them with catches to Bob Taylor, who took a record seven in the innings) and 7 for 48 in the second - 13 for 106 in the match, figures bettered for England post-war only by Laker, Bedser and Underwood - with an innings of 114 as the filling in the sandwich. "It was," said

Wisden, "an extraordinary all-round performance by Botham, whose versatility was in full bloom. There was hardly a session on which he did not bring his influence to bear." It might almost be his cricketing epitaph. In that match, the world was his oyster. It was never again quite as simple as that. The next time he took the field for England, he was captain.