Success matters a lot in the Australian cricket culture and no Australian cricketer right now, no matter how you twist the mathematics, is more successful than

Shane Watson. Yet a surprising number of cricket conversations these days proceed as follows. "Can't quite put my finger on it," some well-meaning fellow will bash out, his eyes crinkling in sympathy and bafflement. The next five words come tripping off the tongue like a Boomtown Rats anthem. "I don't like Shane Watson."

And it is a little baffling. Admittedly this is an odd sort of cricketer: at heart, a middle-order batsman who bowls a lot, who has transformed himself into a top-of-the-order batsman who bowls a bit because the team had a vacancy for just such a Frankenstein.

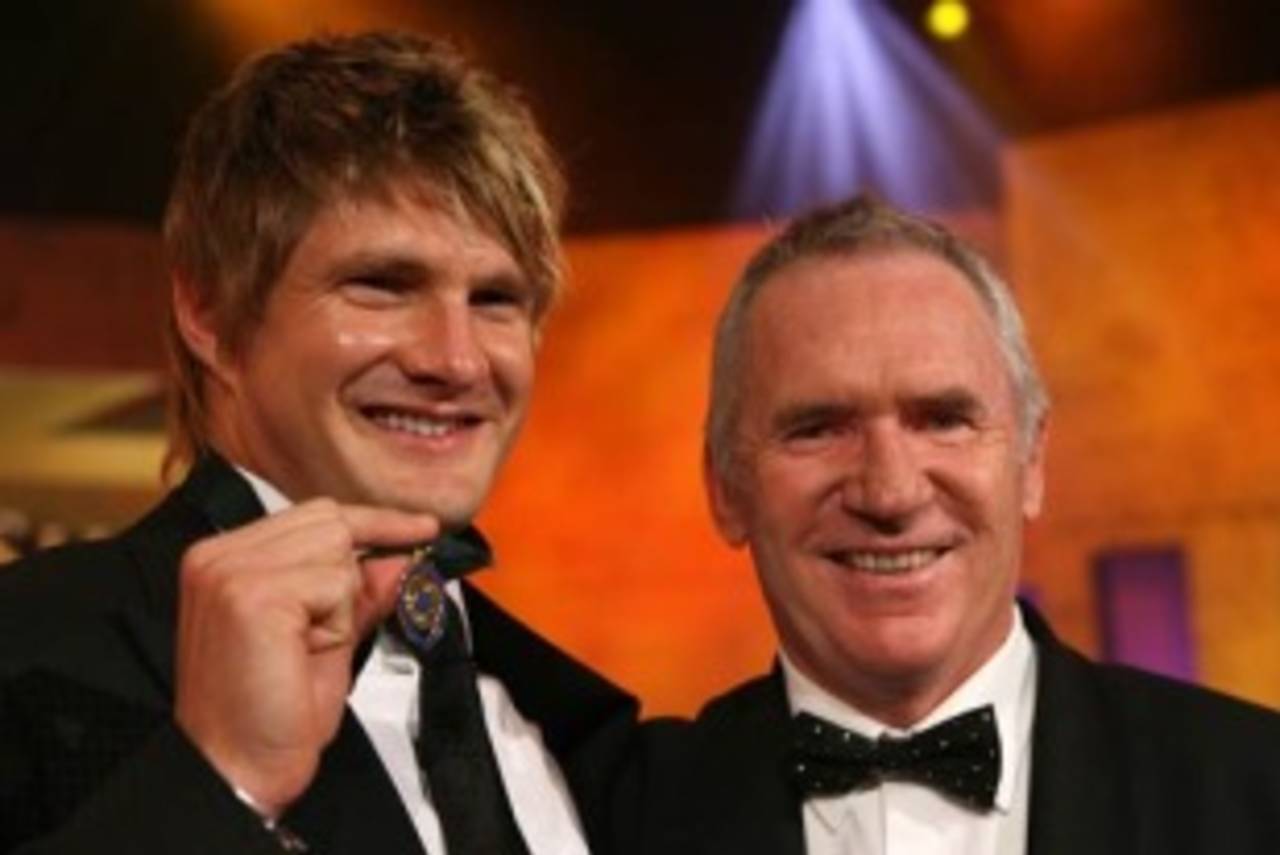

Odder than that, though, is this: Shane cries. When his curtain-rod hamstrings went ping before the 2006-07 Ashes series, Shane's tears kissed the green grass in fat, dewy drops. When he won the Allan Border Medal last summer he sounded like he might choke on them. AB clapped him three times on the back and yanked the ribbon roughly round his neck, and it took all of Shane's froggy might to croak out the words "It's been an amazing ride".

In despair and delight, he weeps and he weeps. It happened again the other day, when he married his TV sports-reading sweetheart at a rich ad man's coastal hideaway, where the C-list hobnobbers and assorted crickerati swayed to Louis Armstrong and the emotional couple vowed to be "partners in crime until the end of time", words they'd penned themselves. "Tears," reported Woman's Day, "welled in the pair's eyes."

It used to be that any cricketer who cried faced gleeful ridicule: especially an Australian cricketer, especially if he happened to be Australian cricket captain. Yet Shane's captain, Ricky Ponting, looked fit to burst out blubbering himself on AB Medal night, so unabashedly proud was he of his blue-eyed marvel. In Ponting, Shane has his most bulldog supporter. In this Australian team, Shane's emotions are not merely tolerated but admired. For the rest of us, this should be a symbol of little boys growing up and a cause for rejoicing. Alas, among the rest of us, admiration for Shane runs not so deep, and you don't need to resort to Google - to the Shane Watson Is A Tool, Tosser and Douchebag societies on Facebook, to the myriad numbskull bleatings about Shane's sexual, hair-product and coffee preferences - to realise it.

That Shane may or may not like lattes is of interest chiefly to shallow idiots. The real issue is this: the ancient, hazy balance between the team and the individual.

In cricket, the team's the thing. This gets pumped into children at their first schoolyard net and ad nauseam ever after. Yet the team's total is only arrived at once you have totted up 11 individual totals. And if your own total is not up to scratch, pretty soon you shall be one individual who has nothing to do with the team. For anyone in such tenuous employment circumstances - even if you're the least self-interested cricketer on the planet, even if you're Keith Miller - the team cannot truly be the only thing. But ideally it should be the main thing. If it's not, you should wear enough fake smiles and sufficiently deadpan a demeanour that people assume that it is.

When Shane Watson plays cricket - when he plays cricket badly, in particular - the hazy balance comes sharply into focus. During the

World Twenty20 final against England, Shane looked like he might cry four times: upon getting out third ball of the match; while rubbing his brow after his fifth and sixth deliveries went for four; as he forlornly fetched his cap after copping a 16-run second-over pizzling; and when the losing crunch past midwicket happened off his bowling. All the while he had about him an air of spitting, cursing, slightly stressed-out gormlessness.

Was he fretting about the team's deep doo-doo? Or about himself and his future prospects and the beastly world?

Not that Shane need fret over his job security. Few batsmen anywhere can pummel bad bowling as matter-of-factly as Shane did last summer, trotting one step forward and driving anything remotely overpitched in an arc between cover and mid-on. But, then, last summer, when Australia somewhat unconvincingly saw off the world's second-worst and fourth-worst Test nations, was what Malcolm Knox has rightly dubbed The Summer of Our Kidding Ourselves. And in shoring up a spot in the team, Shane made stunningly little progress in burrowing a place in people's hearts.

His wee gulps and swallows on Allan Border Medal night had a touching vulnerability to them. Joylessness was a hallmark of his other public utterances. Every microphone up his buttonhole was like a new audition for a deodorant commercial, another chance to come up smelling like roses. Maybe such transparent self-interest was not unprecedented among cricketers; certainly it was gobsmacking.

All the while he had about him an air of spitting, cursing, slightly stressed-out gormlessness

Four times in 31 days, from December 6 to January 5, he amassed

Test scores of between 89 and 97. Yet rather than thinking to himself what a wonderful world it was, Shane seemed to have Neil, not Louis, Armstrong on the brain - as if the nineties were a moonscape mankind had never tiptoed across before.

In Adelaide he went to bed 96 not out. He "slept very ordinarily" and "kept thinking about the four runs I needed". The traditional self-effacing mumble about being happy for the team and just glad to do his bit got a not very big airing.

Hours of sleeplessness ticked by, the sun came up and still the "childhood dream of getting a Test match hundred" filled his every thought.

Then - "that's what engulfed me". Second ball of the morning pitched short. "I thought, here it is." Oh no, it wasn't.

In Melbourne, run out for 93, Shane made no secret of his disinclination to leave or his fury with batting partner Simon Katich. A friend text messaged: "When Peter Sleep got out for 90 at the G in '87 I was sad. When Watto got out today I was delighted, absolutely delighted." No sorrow for Shane, then. No consoling hug, either, for Katich - no "Mate, no hard feelings, not your fault, the team's the thing." Thirty minutes after stumps, it was reported, Shane and Katich had still not spoken to one another.

Here was a soap opera to lead every silly season news bulletin. The 30th anniversary, almost to the day, of another Test ninety was overlooked. Overlooked is probably the way humble

Bruce Laird likes it. On his

first day of Test cricket Laird survived five hours, two blows to his right thumb and four bullies: Croft, Holding, Garner and Roberts. Eventually it got dark, too dark for cricket, but new boys in those days were supposed to be not heard, and certainly not heard squealing for light meters. The inevitable happened. Laird, on 92, played, almost definitely missed and the umpire - it

was dark - gave him out caught behind. One ball later play was called off. Laird did not grizzle, apportion blame or overuse the word "I". "I thought about an appeal against the light, but thought I was hitting the ball well enough to get through," was all he'd say.

You could not invent a more exact opposite of Shane Watson than "Stumpy" Laird. Craggy, hairy lipped, unmuscular, unwaxed, selfless and beloved by all, Laird would spend most of his time batting on the back foot. He married no sports-reading beauty. He made no Test hundred.

Shane has hit one, and the occasional flash of gratitude or good grace might make him a bit more likeable. It is a fine thing that Shane does not pretend to be some person he's not. It will be interesting to see whether Australians ever warm to the person he is.

Christian Ryan is a writer based in Melbourne. He is the author of Golden Boy: Kim Hughes and the Bad Old Days of Australian Cricket