An artist in the super league of left-handers

If you're a South African born not later than the sixties, there'll only ever be one No. 4 for you

Robert Houwing

23-May-2010

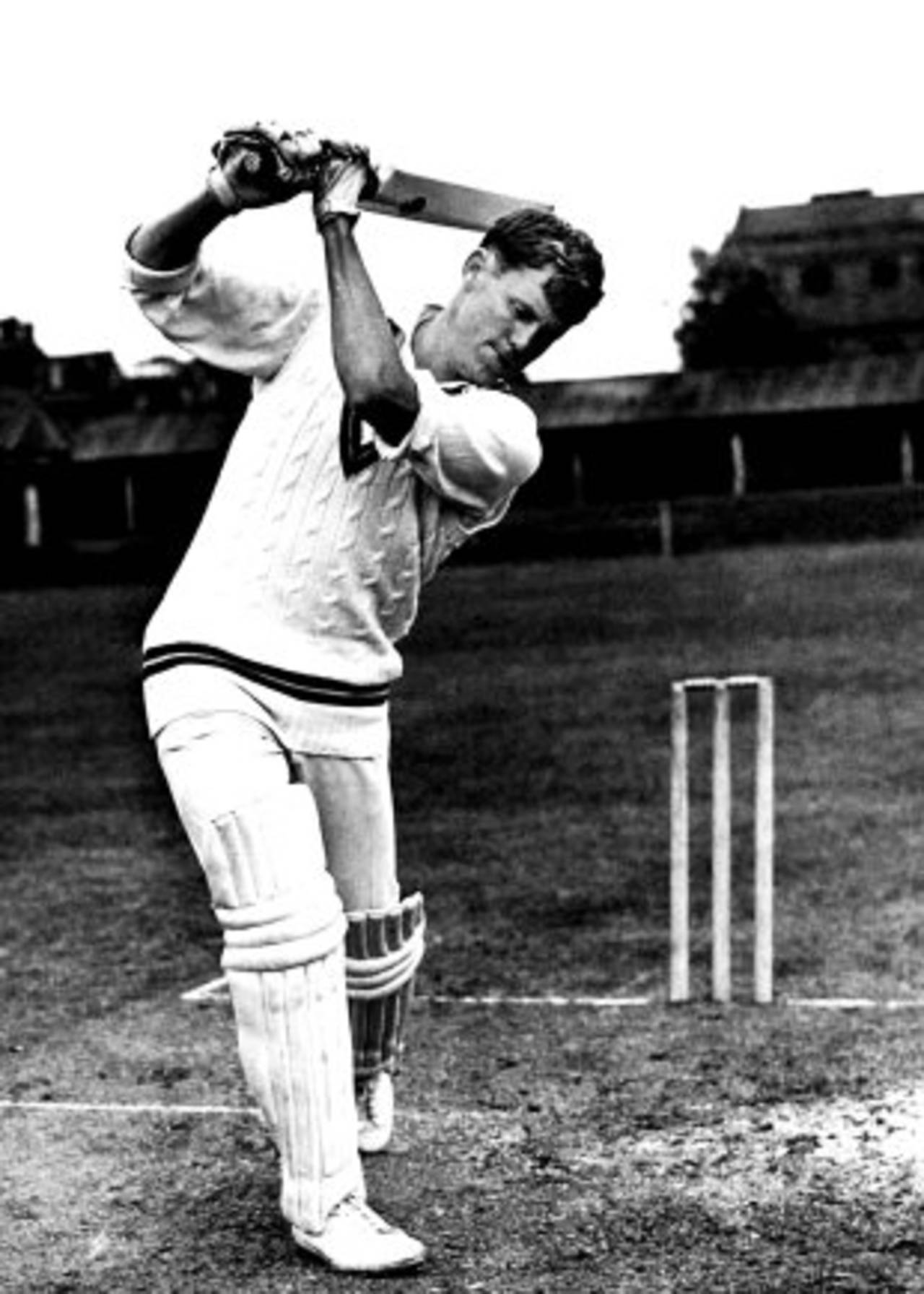

Graeme Pollock: a profound command and aura at the crease • PA Photos

Graeme Pollock is in that elite corps of batsmen who looked elegant just sauntering two paces between deliveries and idly patting down the pitch. In really fanciful dreams you could imagine people paying good money to see that ludicrously limited aesthetic, and only that.

Yet Pollock was no curator, of course. He was rather higher up cricket's pecking order: a master craftsman, an artist in the super league of left-handers. His profound command and aura at the crease were unmistakable.

Among seasoned, cricket-loving residents of the Eastern Cape hub of Port Elizabeth are many who recall with huge fondness and awe Pollock's exploits at club level for Old Grey and how they flocked to witness this general of batsmanship canter into lopsided battle with the huffing and puffing mortals of the local Premier League.

The clubhouse landline would ring with rare monotony: "Are Grey batting?" "What's the score, please?" And particularly commonly and urgently: "Is Graeme in yet?" The surname was gloriously irrelevant.

This was not the stuff of indulgence, of half truth, distorted over the passage of time: the website of Grey High School, where Pollock had represented the 1st XI aged 13, contains an engrossing little confirmation in its "Sporting Legends" section:

"Graeme used to entertain many a Port Elizabeth enthusiast on a Saturday afternoon for Old Grey. Cars used to park all the way around the field and in many areas two, three or four deep. This prompted Dave Butlion (a prolific striker of the ball, who once hit six sixes in an over in club cricket), who batted at five and often had to go in after Pollock to say: 'I would walk to the crease with cars hooting to acknowledge another great Pollock innings; as I took guard the engines would start up, and by the time I scored my first run, the ground was once again empty'."

No. 4 in the order… ah yes, if you are a South African not born later than the Sixties, it is always tempting to brand it not numerically but by calling it unequivocally the "Pollock position" in a Test or provincial first-class landscape. In fairness, there may be a burgeoning modern school suggesting the "Kallis berth", while Daryll Cullinan served the post in attractive, dominating fashion as well, especially if Australia and their legspinner were engaged elsewhere.

But Robert Graeme Pollock was near-synonymous with it, as reflected by all but four of his 41 Test innings being at that station - including his debut in 1963 as a 19-year-old in Brisbane.

Even as he wound up his career at the advanced age of 43 in 1986-87, that slightly bandy-legged but purposeful walk to the crease - accompanied by whispers of excitement outside the ropes - came invariably at second-wicket-down for the fearsome Transvaal "Mean Machine" of the old Currie Cup, sandwiched as he often was between Alvin Kallicharran at No. 3 and the captain, Clive Rice.

For someone whose Test career was suddenly slammed shut at 26, as if with the exasperating purpose a post office might find at four o'clock sharp, Pollock's particularly elongated swansong era for Eastern Province and then Transvaal in an immensely strong and competitive domestic competition went at least a healthy distance in compensation.

"He was like the lucky guy you knew who never got the flu… somehow you always felt Pollock was over the ball; it never seemed to be over him"Hylton Ackerman on Graeme Pollock

They used to advise that you had to snare Pollock early, perhaps jabbing at a lifter outside off stump, to head off a pasting. You could say that of so many batsmen, of course. As his vision dimmed a little, Transvaal's great rivals Western Province used to pin their hopes on big-chested fast bowler Garth Le Roux, renowned for rich harvests in Kerry Packer's World Series Cricket, to dislodge him with a still-newish ball. But if Pollock negotiated this testing little hors d'oeuvre phase, the main course would invariably become a sumptuous dish with his signature splashed all over it.

To have seen notably more of his twilight years, as I did, than his heyday brought mixed emotions: delight at the opportunity to have got some crystal-clear appreciation of what the fuss had all been about in his apartheid-slashed Test career; regret that such a precisely weighted combination of power and gracefulness must have been oodles more pleasurable to the onlooker's eye while he was a younger man.

If Pollock had a hallmark place in the batting order, then he had a signature stroke too: his cover drive. He played it with relish and quite withering authority. Bam! If you were the bowler, maybe only negligibly errant in line and length, it was almost inevitably Goodnight Gertrude.

Pleasingly, the essence of it was far less an extravagant, indulgent follow-through - these days they might call it the bling licence in the shot - than it was his poetry-perfect body position as bat met ball and effectively sent it yelping like a puppy scalded by a tumbling pot of hot porridge. More often than not, a scampered two or three was unnecessary; four would be the sumptuous outcome, with the cover fieldsmen requiring no more than to await the return of the bruised apple from a rope-side steward or audacious schoolboy who'd vaulted the pickets.

Pollock would watch it on its way and barely move. Does that smack of arrogance? The question is posed at this juncture because a compelling aspect of his make-up, some contemporaries insist, is his modesty and even a surprising splash of insecurity.

Ali Bacher, Pollock's captain in the landmark 4-0 whitewash of Australia in 1969-70, clearly recognised the latter phenomenon. "It would have been all too easy to take such a great and consistent player for granted but Ali realised that Graeme, despite his stature in the game, required constant reassuring," wrote recently deceased author Rodney Hartman in Ali: The Life of Ali Bacher. "As a captain, he would also play up the 'threat' of Barry Richards to push Graeme into maintaining his position as the leading batsman."

How fitting, then, that Pollock and Richards - the latter widely considered South Africa's right-handed equivalent as a batting untouchable - were responsible between them for arguably the most enthralling one-hour passage of Test play by that country.

Word of mouth, newspaper cuttings or token flashes of wobbly newsreel are the lone conveyors of description of their assault on Australia after lunch on day one of the second Test against Bill Lawry's Aussies at Kingsmead in February 1970: television, you see, with its window to the wider and critical world, was deemed until 1975 a poisonous tool to be spared the minority white-led South African populace. But those who saw it are unanimous about the majestic destruction the two batsmen sowed on a visiting arsenal that included Garth McKenzie and Johnny Gleeson, plundering more than 100 runs in the heady period at a before-its-time rate of some six runs to the over.

Eddie Barlow, later out for one at No. 5, reputedly muttered that there was "no price" batting after Richards and Pollock's carnage. Richards made a scorching 140 at a strike-rate of 85 - that, too, rather a novel development then - while Pollock went on to a then-South African record 274 with 43 fours. Percentage of those boundaries through his most cherished covers is an elusive statistic, alas, with wagon wheels perhaps considered more synonymous then with the country's gritty Afrikaans Voortrekkers of the 19th century. The Wisden Almanack bears the following observation: "His concentration never wavered and he attacked continuously."

Pollock's combat against England tends to instantly brings up two words: Trent Bridge. In bluntest terms, the second of three Tests in 1965 - South Africa crucially won in Nottingham, eventually stealing the series 1-0 - was one of those where people just felt "privileged" to have seen Pollock in fullest cry.

Graeme Pollock was inducted into the ICC Hall of Fame in 2009•Getty Images

The encounter was a massive triumph for the family name, with his fast-bowling brother Peter landing 10 wickets. But Graeme's first-innings 125 at not far off a run a ball, and under fairly precarious circumstances for his team, is carved deep in South African legend. The innings, punctuated by the gorgeously uncluttered mindset of 21-year-old Pollock, badly needed the disproportionate weight of his contribution: South Africa were bundled out well inside the first day for 269 after winning the toss. Captain Peter van der Merwe was second top-scorer with 38, and his fresh-faced partner Pollock wholly dominated their partnership of 98 for the stabilising sixth wicket, hogging 91 of those runs.

"He was like the lucky guy you knew who never got the flu… somehow you always felt Pollock was over the ball; it never seemed to be over him," the late Hylton Ackerman, standout coach and another South African left-hander who represented a World XI in 1971-72, once enthused to me.

Even in this era of Test batsmen being able to fill their boots at times against a battery of weaker nations, Pollock (60.97) remains second only to Don Bradman for highest career batting average.

All but one - New Zealand in Auckland in 1964 - of his 23 appearances came against either England or Australia, although of course he lives with the regret of never having faced the dustbowl wiles of Indian bowlers or chin music of the Caribbean's best shock bowlers.

Pollock was and is a notably deep respecter of cricket's heritage and etiquette. Always sensitive to the societal injustice around him at the height of apartheid's oppressive choke-hold, South Africa's officially branded cricketer of the last century stayed a generous step behind Dolly when he and Basil D'Oliveira, the iconic man of colour who had retreated to England to pursue his own Test career, took to the Newlands turf to open the World Cup of 2003.

A firm patriot, he never sought employment abroad at any stage of his career: it is strange to see "South Africa, Eastern Province and Transvaal" as his sole life ports in serious cricket.

Graeme Pollock may be 66, but in Port Elizabeth you can still almost picture people purposefully turning the keys of their Ford Anglias or Austin 1155s in suburban driveways. "C'mon, let's dash, dear… Graeme's just in for Old Grey."

Robert Houwing is chief writer for Sport24.co.za in South Africa and former editor of the Wisden Cricketer SA