The rebel tours of South Africa that took place between 1982 and 1989 are events which, almost three decades on, still reflect badly on the game in general and those involved in particular.

By the start of the 1980s the world was increasing pressure on South Africa's apartheid regime with sporting, political and commercial boycotts. But there were glaring inconsistencies. Multi-national business continued to openly trade with and operate inside the republic, and in sport double standards were even more apparent. While cricket against the South Africans and individual participation inside the country was banned, golfers, tennis players and even rugby teams carried on as usual with virtual impunity.

Some cricketers were willing to tour and play in South Africa despite widespread public opprobrium and the threat of repercussions from those running the game. The reason was simply that the sport-starved administrators in South Africa had piles of cash on offer, and most people have their price.

South Africa's last official Test came in early 1970, swiftly followed by the abandonment of their planned tour of England later that year. When Australia, after massive protests, scrapped a visit by the South Africans in late 1971, their cricketing isolation was complete.

Sides continued to tour - none official but containing a cross section of leading players - and quite a few individuals headed to South Africa in the winter to play or coach. As strange as it may seem now, throughout the decade there were attempts from within South Africa, which gained a fair level of support outside, for them to be readmitted to international cricket.

Two things changed. Firstly, the advent of Kerry Packer's World Series Cricket, which - wrote Gideon Haigh - "made the unthinkable thinkable; that men would play for money rather than merely national pride".

The second was a visit from a far-from-unsympathetic fact-finding group sent by the ICC that toured the republic and concluded that cricket had become completely integrated. The conclusion was that strong representative sides should start touring straight away and the profits from such events should be ploughed back into fostering multi-racial cricket in South Africa.

The report never saw the light of day, largely because India, Pakistan and West Indies opposed it, arguing, not unfairly, that the ICC delegation had seen what its hosts had wanted it to see.

For South Africa, the decision not to make the findings public was in effect the nail in the coffin. Those involved in the game accepted that as long as apartheid remained there could be no normal sporting relations with the outside world. Privately, England board chairman Doug Insole told the South African Cricket Union's Ali Bacher that England, seen as the most likely backer of the South African cause, could not intervene. "If we did it would be the end of English cricket," he said. "The black nations would not play against us."

"The English cricketers are already becoming known as the Dirty Dozen"

Labour MP Gerald Kaufmann in a debate in the House of Commons the day after the tour became public

Bacher reported back to his board that there was "no way back through the front door". At that point the alternatives became the only option. SACU realised that to lure players to undertake tours that could potentially finish their careers, large sums of money had to be offered. Equally, for them to be a big draw in the country, leading names had to be involved. The whole process also had to be carried out with the tightest secrecy.

West Indies, the leading side in the world at the time, were the prime target but politically the least likely to be bought. Nevertheless, approaches were made to some of their top stars. Almost all were brusquely dismissed.

The next most likely group was England's players, a number of whom already had at one time or another played and coached in South Africa. Their political objections, with a few exceptions, were not nearly as strong.

In his book The Rebel Tours, journalist Peter May claims that on the 1980-81 tour of West Indies six players - Ian Botham, Geoff Boycott, Graham Dilley, John Emburey, Graham Gooch and David Gower - signed a letter expressing interest in a "quiet, private" tour. Within a few days the whole idea became far bigger news when Robin Jackman was refused admission into Guyana because of his links with South Africa, and England's Test at the Bourda was cancelled.

Peter Cooke and Martin Locke, two South Africans acting as organisers, continued their stealthy approaches to players. At the end of the 1981 English season the Test & County Cricket Board found out that John Edrich, a selector, was organising a private Counties XI tour to South Africa. It immediately issued a warning that those involved were putting their "careers in jeopardy" and the venture quickly collapsed. Behind the scenes, the SACU plans for a tour between the end of the English summer and England's tour to India in November were quietly put on ice.

Every run they score will be a blow to someone else's freedom

An editorial in the Daily Mirror

However, there was a degree of resentment. Players argued that they were being deprived of earning money outside the five-month season for which they were contracted. What, so the argument went, was the difference between what they were doing and the businesses that continued to openly trade inside the republic?

In October 1981 the six England players were joined by three more - Mike Gatting, Alan Knott and Bob Willis - who expressed interest in a newly arranged trip before the start of the 1982 English summer. In the interim, the Indian government had refused to allow Boycott and Geoff Cook into their country as part of the England side because they had visited or coached in South Africa. The tour eventually went ahead,

but only after endless diplomacy at the highest levels.

Discussions between Cooke, Locke and various players rumbled on during a tedious six-Test series. Gatting withdrew after the first Test and then Botham, who one of those involved later said was offered "the moon", during the second. He was widely advised the amount he could earn from personal endorsements after his remarkable summer in 1981 would far eclipse income from any rebel tour.

The main sponsor - Holiday Inns - had made their support conditional on Botham being in the tour party, and when Gower withdraw, for financial rather than moral reasons, they pulled out. With big names opting out and no money, the whole plan was falling apart. When Boycott returned home early from India after the fourth Test, he believed the whole scheme was dead in the water.

As the England squad headed to Sri Lanka to play the inaugural Test in that country, Cooke and Locke got the break they needed. Graham Gooch, disenchanted after the India series, agreed to join them. Nevertheless, there were still only four confirmed rebels.

One thought kept flashing across my mind: I could never have looked my mate Viv in the eye this season... I won't be earning the £50,000 I was promised in South Africa, but at least I'll be able to hold my head up when I play county cricket again.

Ian Botham's column in the Sun. He later claimed the article was published without his consent

In a reverse of the situation when Packer was recruiting players using the then England captain, Tony Greig, this time it was the captain - Keith Fletcher - who was in the dark as meetings and offers took place behind his back. Fletcher finally found out when he was offered £45,000 to captain the side soon after he arrived back home.

Cook, John Lever and Derek Underwood signed up, and back in England they were joined by Mike Hendrick, Wayne Larkins, Chris Old and Peter Willey. Dennis Amiss and Les Taylor were the last to join. On February 20, Locke and Cooke visited South African Breweries in a bid to get them to underwrite all the costs. A deal was struck within an hour.

England landed back at Heathrow airport on February 24 with the whole South Africa tour still a closely guarded secret. Cooke and Locke were at the airport to meet the England players as they had not signed any contracts. The situation soon turned farcical as the squad was met by board officials. "It was a case of hiding behind pillars and having fleeting conversations with them," Locke admitted. "In the end we decided we couldn't do anything worthwhile there." Over the next two or three days Cooke and Locke travelled the country, getting contracts signed.

Willis, however, withdrew after he got back and found he had been offered a more beneficial contract by Warwickshire. Cook was also persuaded by the TCCB, which had finally got wind of what was happening and was desperately trying to talk those involved into changing their minds, to pull out

But at the same time the organisers landed an even bigger fish - Boycott. "I came to the conclusion I had no choice and very little to lose," he later said, with reports circulating that he was about to be sacked by Yorkshire and his England career all but over after he quit the India tour.

"The suggestion he had opted out of the tour on moral grounds was unnecessary and puke-making"

Geoffrey Boycott on Botham's withdrawal from the tour and subsequent attacks on those who went

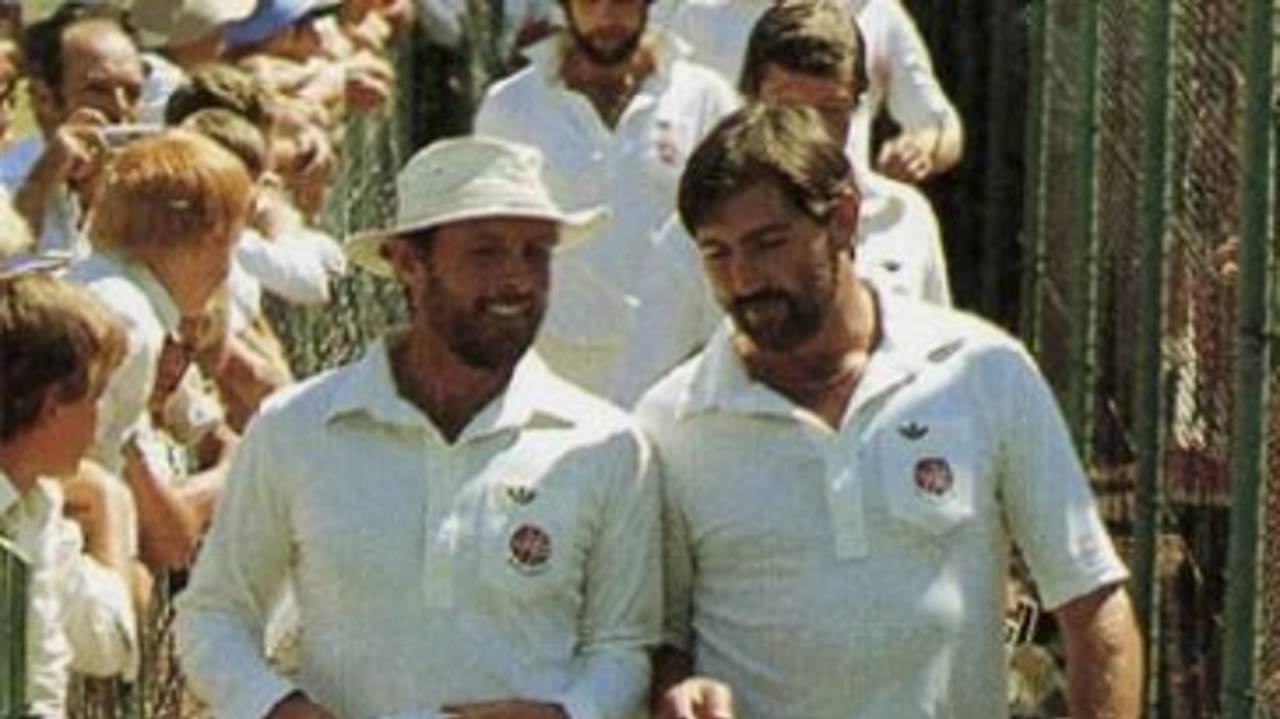

The news finally broke when seven of the squad landed in Johannesburg on March 1, followed a day later by three others (two were already there). The 12 were being paid between £40,000 and £60,000 each.

If they expected a brief flurry of news and then to be left alone, they were soon to find out the consequences of their actions were to be far more serious. In London, questions were raised in Parliament, the minister for sports accused those involved of deception, and the general reaction was of dismay.

In South Africa the authorities made no end of political capital, claiming it signalled the return of international cricket. With the exception of Botham, so the story went, it was the full England XI, and Test caps were awarded to the home side for the "Tests".

Even as the tour kicked into life the organisers realised they needed more talent, especially batsmen. Overtures were made to several players, including another to Botham, but in the end the three who were signed (Geoff Humpage, Bob Woolmer and Arnie Sidebottom) were hardly big-name attractions.

The series was a damp squib, although the South African public, at least the white minority, along with the media, initially lapped it up until the one-sidedness of it all brought home the reality that the England XI was anything but representative. The ageing rebels were no match for a rampant home side and were comprehensively beaten.

The rebels returned from their four-week tour considerably richer but with a three-year ban from all international cricket slapped on them by the TCCB. As a deterrent it was not overly effective. Emburey returned to the republic with the second England rebel side in 1989-90 and was hit with another three-year ban. Both times he was recalled by England after serving out his punishment.

England squad Graham Gooch (capt), Dennis Amiss, Geoffrey Boycott, John Emburey, Mike Hendrick, Alan Knott, Wayne Larkins, John Lever, Chris Old, Les Taylor, Derek Underwood, Peter Willey. Geoff Humpage (March 6), Bob Woolmer (March 8), and Arnold Sidebottom (March 15) were signed up after the tour started, taking the final number of players to 15.

Is there an incident from the past you would like to know more about? Email rewind@cricinfo.com with your comments and suggestions. Bibliography

The Rebel Tours by Peter May (SportsBooks Limited, 2009)

Boycott The Autobiography by Geoffrey Boycott (Corgi, 1987)