Jackson or

Bradman - who to pick first? It is a tantalising choice, yet also a puzzle, and it happened not in make-believe but in October and November of 1928.

Four times in four weeks, again and again and again, the two shiniest talents in all of New South Wales, one from the grime-streaked dockside suburbs, the other from the tulip-growing highlands, batted off for supremacy. The prize was a place in the Test side to meet Percy Chapman's Englishmen. First they had to negotiate an official trial outing, for The Rest against an Australian XI, where it was Archie Jackson who outdid Donald Bradman, but narrowly, inconclusively. They were sent back to the state team, for two more matches, and it was Bradman was the power. Jackson cracked two fifties, Bradman three hundreds, enough almost for the selectors to say that was that.

But not quite. A blister of doubt remained: he could plunder the hapless, this young Don, but who had the steel for a crisis - Jackson or Bradman?

Sydney Cricket Ground was the stage for the fourth and most exacting test of their mettles. Chapman's men were to play an Australian XI. Except the Victorians, insulted by the offer of a pound a day for expenses, did not show up. Selectors Bardsley, Bean, Dolling and Hutcheon all did. Jackson went in at four, Bradman at five. Jackson, pale, and worryingly lean, had recently turned 19; Bradman was 20. When a third wicket fell they were at the crease together. Soon it was the last over before lunch.

Harold Larwood bowled and Bradman edged - and got lucky. The ball bounced in front of third slip and Bradman was away, 4 not out. Two balls later Jackson edged Larwood and third slip caught it knee-high.

No one reached 40 that day; no one but Bradman, that is, who batted slower than he ever had or ever would again, unflustered by the "have a hit" pleas of the 11,000 watching, for 58 not out. Within a fortnight Bradman was in the Test team. Jackson had to wait. And time was something of which Jackson had too, too little.

Picking Bradman not Jackson was a guess, but it was as educated a guess as could possibly be arranged. That was the ritual. Australia's best regularly tested themselves against Australia's best in the Sheffield Shield. Each Shield team played a game against that summer's tourists. The tourists, before the opening Test, would face a composite Australian XI in what was effectively a selection trial. Sometimes a composite Australian XI would play another composite Australian XI, called The Rest, in a second selection trial. Later, if a big overseas tour was coming up, a third selection trial might be whistled up between, say, Ryder's XI and Woodfull's XI. This would double as a testimonial fundraiser for out-of-penny old cricketers.

Selectors were the winners. Put through so gruelling a cross-examination, any budding Test player with frailties could not hope to hide them from the selectors. Crowds were big and the stakes high at these selection trials, where dreams sometimes came true and other times came a cropper.

Tall

Lisle Nagel, a swing bowler, got to know both sensations. Hurling into the wind, his bandaged elbow flapping - he'd hurt it cranking a car - Nagel took eight wickets in 10 overs for an Australian XI against MCC, catapulting himself into the opening stoush of the Bodyline series. His bounce and swerve were awkward, his prospects looked bright. A year later, relaxing between overs for Richardson's XI versus Woodfull's XI, Nagel perched beside Tiger O'Reilly in slips. "He turned to tell me something," O'Reilly would later recall, "and ricked his neck. I never saw him play again."

Big-swinging

Les Favell's last chance of a maiden Ashes voyage hinged on a 1955-56 selection shootout between Johnson's XI and Lindwall's XI. Favell's mate, Gil Langley, mucked up a simple stumping chance offered by Favell's rival, John Rutherford, who proceeded to make 113 seldom pretty but pretty remorseless runs. Favell himself, in reply, got as far as 4 - then, calamity. "Alan Davidson," he rued, "produced one of his wizard balls which swung about a foot in the last yard… England was getting further away." Rutherford rubbed it in by fiddling out Neil Harvey on 96.

Stuff-ups are run-of-the-mill nowadays, in the era of not many tour games, no selection trials, no best-against-the-rest testimonial matches, no Test stars slumming it in domestic ranks, zero rigour to the selection process. Zero is just about the average Sheffield Shield attendance

"Hey! You're not supposed to be taking wickets."

"That's right. Isn't it a funny game?"

Few laughed when Frank Ward, not Clarrie Grimmett, won a seat on the boat to England in 1938. Bradman's greatest stuff-up, they cried, and they were right no doubt - or almost no doubt, for actually in five lead-up matches, bowling a comparable number of overs, for the South Australian team, Bradman's team, Ward took 22 wickets, Grimmett 21. Dumping Grimmett was theoretically consistent with the Australian selection ethos: watch a player at length, in all possible conditions, against rich and varying opposition, then pick on form.

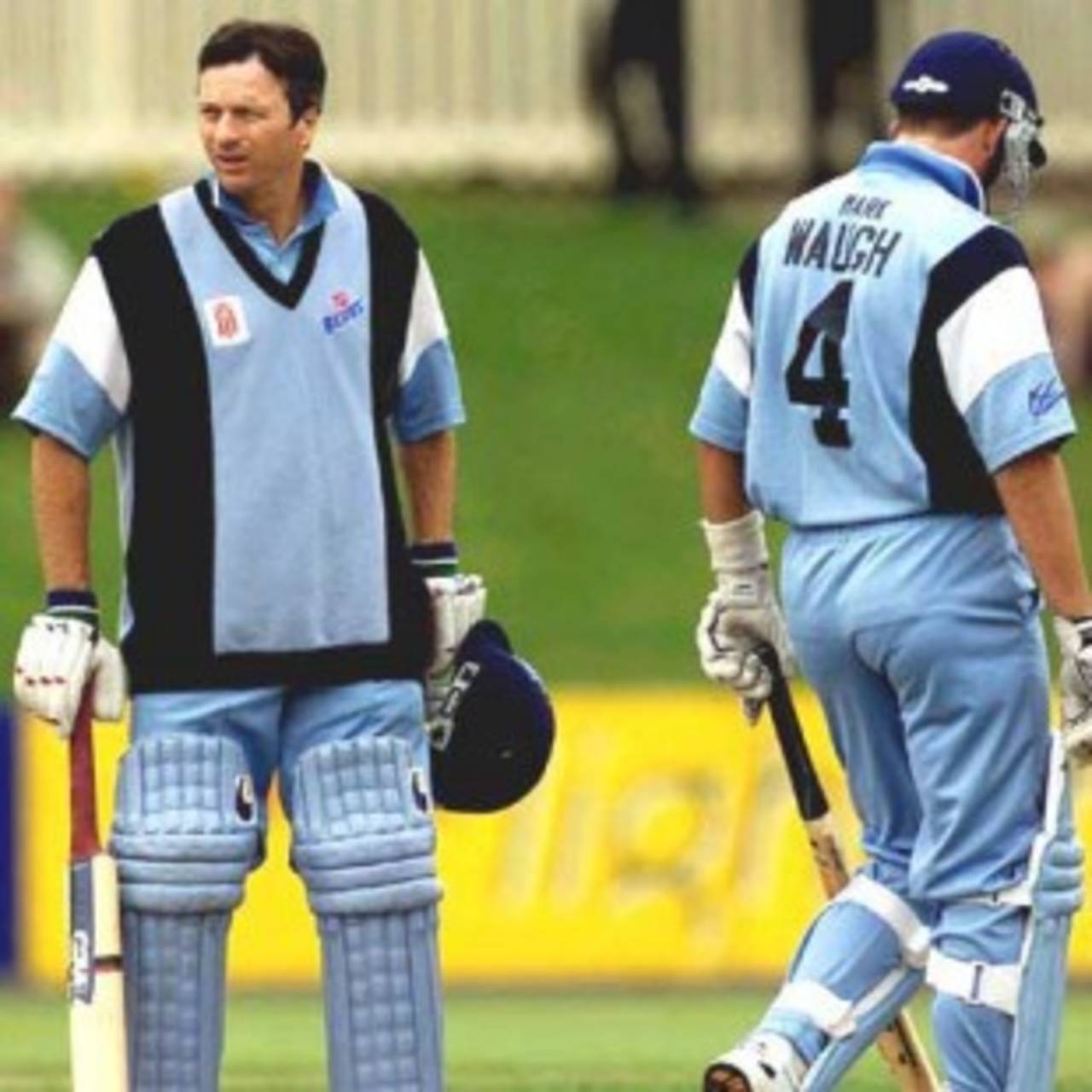

Stuff-ups are run-of-the-mill nowadays, in the era of not many tour games, no selection trials, no best-against-the-rest testimonial matches, no Test stars slumming it in domestic ranks, zero rigour to the selection process. Zero is just about the average Sheffield Shield attendance. Yet as recently as 1992-93 an Australian summer began with Dean Jones, Damien Martyn and two Waughs fighting out a slightly bitter and very public five-week tussle for three batting spots. "You're ending his Test career," warned selector Jim Higgs when Jones was the unlucky one left out. And they were. But at least the selectors had reason to think, rather than blindly hope, that this might be for the best.

Seven months after Bradman pipped Jackson, a New York laboratory hosted the first public demonstration of colour TV. Colour TV's demands twist cricket further out of shape with each passing year. Players earn thousands by the hour, and teams are now called Cobras. But if the money and the gimcrack are what matters, and no one watches, no one listens out for the score on the radio, no one cares, then it's conceivable that we had it better in 1928 than we do in 2009.

And pity the modern selector. Half the positions in Australia's battling Test side - a couple of batsmen, the keeper, two or three bowlers - should be set not in stone but in quicksand. Yet probably there shall be no new blood when next the selectors meet. Because how can the modern selector judge who is a future Test cricketer and who isn't? How's a selector to know a cricketer, to get a feel for a cricketer, if he doesn't get to really see the cricketer?

Then again, it could so easily have been Bradman's edge that carried to third slip's knees and Jackson's that rolled away for four. It is an imprecise business, selecting cricketers.

Christian Ryan is a writer based in Melbourne. He is the author of Golden Boy: Kim Hughes and the Bad Old Days of Australian Cricket, published in March 2009