Cricinfo's all-time England XI: Jack Hobbs, Len Hutton, Wally Hammond, Ken Barrington, Kevin Pietersen, Ian Botham, Alan Knott, Derek Underwood, Harold Larwood, Fred Trueman, Sydney Barnes.

My congratulations to the adjudicators. Such a huge selection challenge was fraught with difficulty, but to my surprise there is no serious cause for dissatisfaction in this all-time England XI. The judges have considered some key factors, such as the challenging unprotected pitches upon which the earlier players played, particularly when the surfaces were almost unusable after rain. More than once Jack Hobbs and his celebrated England opening partner Herbert Sutcliffe batted for hours on bowlers' pitches, using their sensitive wrists and high skills to survive with "touch" batting, playing the dead bat or punishing the poor delivery or withdrawing their lightweight bats from danger. For about 40 years pitches have been protected. Worse still, they are prepared today with the blatant intention of promoting the batsman's welfare in order to maximise gate takings. How we smiled when two Test matches in England this summer finished in three days.

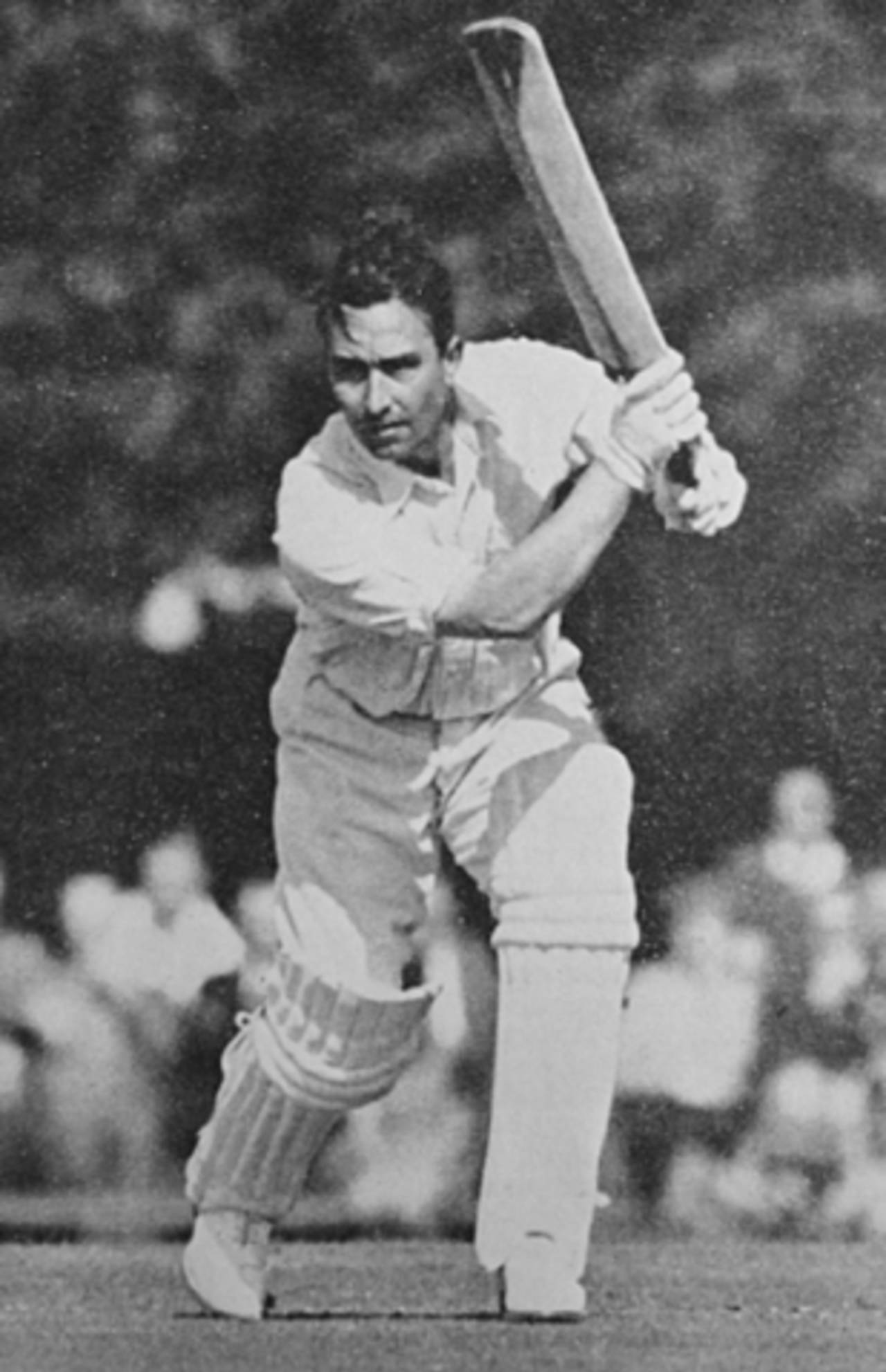

Batsmen like Walter Hammond and Len Hutton made some mighty scores, but they were also famous for some of their shorter innings, played in extremely difficult circumstances after rain. It may be frustrating for the moderns to be denied the chance to display that vital extra skill when the ball is leaping and shooting off imperfect surfaces. Perhaps some of them might have developed that special technique to survive. We shall never know. It's their bad luck - and ours.

The one modern with a place in the top five, Kevin Pietersen, thoroughly deserves his place, though I suspect there are doubters out there. It seems to me that the feeling of anticipation as well as confidence felt by England fans when he strides out to bat compares with that felt in the 1930s when the great Hammond went to the middle. KP has been dominant in the same way, even if he hasn't (yet) put so many double- and triple-centuries in the book. Watching him in that first phenomenal Ashes series of 2005 caused me to wonder just how he did it. I think the key is that long torso. He can lean some way further forward than other men of his height: the hips are comparatively low. He commands a bowler's length for him. Hammond was the perfectly shaped cricketer. KP perhaps owes his success to being unusually built.

Ken Barrington is often forgotten when England's best are being discussed - a criminal oversight. Originally a dasher, he reclaimed his Test spot and became the concrete foundation. Tough, vigilant and good-humoured, he is the batsman most of us long for whenever today's England team flounder.

Such desperate thought also often embraces one who failed to make the all-time XI, Geoffrey Boycott, who simply had too much competition for a place here as an opener. Barrington too had many rivals for the No. 4 or 5 position, including the wonderful Maurice Leyland and Patsy Hendren and, saddest of omissions, Denis Compton. This is the sort of dilemma that has judges pleading for extension: might it perhaps have been the all-time best fifteen?

It may be frustrating for the moderns to be denied the chance to display that vital extra skill when the ball is leaping and shooting off imperfect surfaces. Perhaps some of them might have developed that special technique to survive. We shall never know. It's their bad luck - and ours

I can imagine the outcry had Ian Botham not made it. He can't have been chosen on the basis of that one amazing 1981 Ashes summer alone, for nobody else was selected on such a narrow basis. You need to be quite young not to have vivid personal memories of how English spirits were lifted when this chap charged at the "enemy" with bat or ball in the late 1970s and early 1980s. His was a robust and highly patriotic brand of cricket, and while somebody who is still regarded as The Greatest Cricketer - WG Grace (downgrade him at your peril) - did not play in quite such a nakedly physical way, he would have nodded in approval at the defiant, aggressive overtones.

Alan Knott is an informed inclusion. He was not only seemingly the perfect wicketkeeper but he made runs, which is now regarded as an essential requirement. His Kent and England colleague Derek Underwood was lethal on a rain-affected pitch and tight on a batsman's paradise, so irrespective of where and when this ethereal cricket team takes the field, it hardly matters.

A frontline attack of Larwood, Barnes and Trueman is the stuff of nightmares. Sydney Barnes had the advantage of uncovered pitches, but was not allowed lbws to balls pitching outside the line of the off stump. It's reasonable to assume that he would have been just as phenomenally successful today as 100 years ago. Certainly his force of character was overwhelming, on a par with Dennis Lillee's, if you can visualise it.

Harold Larwood, another who bowled when lbws were so limited, has often been voted as the greatest fast bowler of all time, so it would have been a major shock had he missed selection. Indeed, it would have discredited the exercise.

From the other end: FS Trueman. Not much in it between him and Larwood, though Fred had the gift of the gab. Since cricket these days is played as much with the mouth as the bat and ball, FST would flourish. And like the other bowlers, he would also have relished the drinks and towels provided at third man between his overs. Modern cricketers are pampered, though that is not precisely the language Fred would have employed.

With only two of these elite cricketers having played for England in the past 27 years, the adjudicators seem to have concluded that skills have diminished. Or might it be that the modern players have been denied the chance to demonstrate their fullest potential, now that, with lifeless pitches and slow over-rates, the game has undergone a form of anaesthesia?

David Frith is an author, historian, and founding editor of Wisden Cricket Monthly