|

The old switcheroo: Pietersen gets left-handed

© Getty Images

|

|

"Find out where the ball is. Go there. Hit it." Such a piece of batting advice, credited to the great turn-of-the-century strokemaker Ranjitsinhji, was simplistic almost to the point of absurdity, but it worked for Ranji and it would appear to be a philosophy that Kevin Pietersen follows, too, perhaps with the addition of the words "as hard as you can". Pietersen's

brace of unorthodox sixes off Scott Styris in the first one-day international against New Zealand at Chester-le-Street in June, cack-handed yet controlled, showed again why he is the master inventor of his day, as wily and ingenious with the bat as Shane Warne was with the ball.

It was the shot heard round the world. Yet if Pietersen's audacious switch-hitting at the Riverside had misfired, the

gasps of awe from Durham to Delhi could easily have been replaced by laughter at such vain foolishness. Even his captain winced when Pietersen changed his grip to that of a left-hander as Styris ran in to bowl the third ball of the 39th over and slog-swept it for six over deep backward point (or what had been called deep backward point until Pietersen decided he was a southpaw). "I covered my eyes as soon as he turned his body around," Paul Collingwood admitted. Four overs later Pietersen repeated the trick, hitting a Styris' ball over long off.

It takes bravery, bravado and sheer bloody-minded self-belief to attempt such a stroke. Few have the strength or the timing to hit so cleanly off their wrong side, but while Pietersen's extravagance delighted spectators, appalled some former fast bowlers, and sent the MCC law-makers

into conclave to decide on its legality, the stroke was not quite as innovative as Pietersen claimed. For a start, he had played it himself two years earlier, switching hands before slogging a ball from Muttiah Muralitharan into the stands

at Edgbaston. Middlesex fans swore they had seen a young Jacques Kallis perform the feat when batting for them at Uxbridge in 1997, while some recalled that Craig Macmillan used to try it for New Zealand. Going even farther back, Pelham Warner wrote in the

Cricketer in 1921 of Percy Fender giving "some amusement by hitting [Warwick] Armstrong back-handed on the off side".

Inspired chaos

New or not, it caught the imagination, and in cricket nets up and down the country in the days after

Pietersen's switch-hit wizardry, schoolboys and grown men were trying to copy him. David Houghton, who has been working as a batting consultant for the ECB at the National Cricket Performance Centre at Loughborough, praised Pietersen's audacity but said he worries that

children would try to "sprint before they can walk".

| |

|

|

|

| |

| The idea of the shovel shot is believed to have developed almost 100 years ago when an Australia Test wicketkeeper named Sammy Carter used the stroke to hoick balls over his left shoulder |

| |

"The odds with that shot are immensely in favour of the bowler," Houghton warns. "Pietersen is a one in a million and I'd advise most children not to be preoccupied with all the clever stuff. A lot of very good players score a lot of runs with just the basic shots, and if a youngster comes to me and asks me to help him try some innovative shots, then I have a checklist of the shots they must be able to do first."

But batsmen have always sought to gain an advantage by trying something unexpected, as much as

bowlers try their own new tricks. Take Fuller Pilch, the greatest batsman of the early 19th century, who invented aggressive forward play. Until Pilch, batsmen tended to let the ball come to them. This Norfolk-born innovator had little patience for such play, which on poor pitches carried danger, and so developed the idea of coming well forward to the pitch of the ball and playing it away in front of the wicket.

"Pilch's Poke" caught on and was described thus by Arthur Haygarth in Scores and Biographies in 1862: "His style of batting was very commanding, extremely forward, and he seemed to rush to the best bowling by his long forward play before it had time to shoot or rise or do mischief by catches."

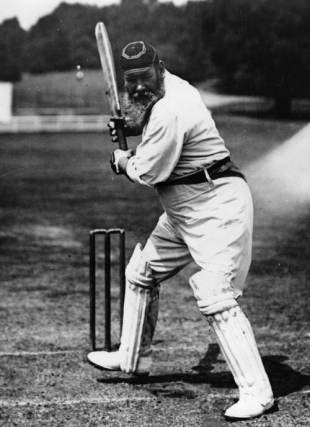

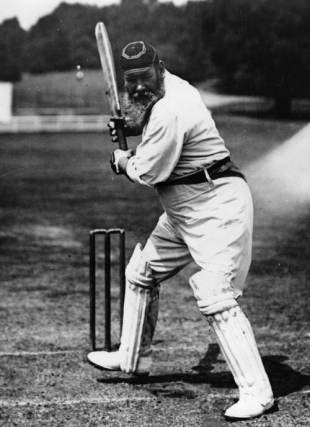

Doctored shots

WG Grace was another innovator, the first to be comfortable playing both forward and back. Taking an unusual stance, with his left foot turned almost perpendicular to the right and often pointing his left toes skywards, Grace stepped forward and back with equal ease, treating the ball always as the subject of his mastery. Intriguingly Grace appears to have been the first to use a double backlift, in the same fashion as Brian Lara more than a century later, taking the bat to hip height at first and then hoisting it higher for added aggression if the ball was there to be attacked.

|

Grace had a double back-lift and was equally comfortable playing front or back

© Getty Images

|

|

Yet the Doctor still tended to play straight. It was his elder brother, EM, who was characterised by

an ungainly but effective style of hitting to leg with a cross-bat stroke, apparently because he

had used too heavy a bat as a child.

Ranji, observing Grace play, wrote that "he revolutionised cricket", adding: "He turned an

old one-stringed instrument into a many-chorded lyre." Yet the Indian prince would add his own

notes to the composition. Before the 1890s, batsmen treated balls that were missing leg stump with

disdain. It took Ranji to realise that it offered a new means of scoring runs.

With supple wrists and immaculate timing Ranji learnt to whip the bat across the front of his pad and steer balls off his legs - and even from in front of middle stump - to the fine-leg boundary.

Combined with the late cut, another Ranji innovation, the Sussex batsman became the first man to make 3000 runs in a season, in 1899, and repeated the feat in 1900. Some thought the leg glance to

be an ugly, immoral stroke, but no less a judge than Neville Cardus praised it as "lovely magic". What would Cardus think of Pietersen?

The batsmen separated by a century were similar in many ways, both outsiders brought into the England team, both quickly elevated to celebrities.

When Ranji went on his first Ashes tour in 1897-98, scoring 175 in the first Test, he was made into a hero and marketing men instantly cashed in with Ranjitsinjhi-branded merchandising. Is it so

different from the dash for cash in today's Indian Premier League?

Repeating history

Wisden echoes the same caution about Ranji as Houghton does today about Pietersen. "He can scarcely be pointed to as a safe model for young and aspiring batsmen," reports the 1897 Almanack. "For any ordinary player to attempt to turn good-length balls off the middle stump as he does would be futile and disastrous."

Boldness, adaptability and quick hands are what set the innovative batsmen apart from mere mortals. Take such strokes as the uppercut, a shot developed by Eddie Barlow in the 1960s and perfected in the opening overs of one-day games by batsmen such as Sachin Tendulkar and Sanath Jayasuriya, who use it to counter the extra bounce of fast bowlers and to take advantage of the fielding restrictions. Lesser men would find that they keep edging to slip or gully but those who can play the uppercut well reap rewards.

| |

|

|

|

| |

| Some thought the leg glance to be an ugly, immoral stroke, but no less a judge than Neville Cardus praised it as "lovely magic". What would Cardus think of Pietersen? |

| |

Then there is the cross-court flick - or what became known as the flamingo shot after Pietersen used to play it so often on one leg. Again, it is a way of countering a short-pitched ball, forcing it away

on the on side with turned wrists rather than risking a pull.

Few would dream of coaching such a stroke, yet even as long ago as 1952 we find some degree of licence allowed by the hallowed MCC Coaching Manual. "A too exclusive concentration on straight play ... and the coach may well have the mortification of seeing his pupils playing with immaculate rectitude but beaten by opponents in whom a good deal of 'the old Adam' survives." That is Adam of Garden of Eden fame, rather than the later Adam whose cross-batted strokes around the world ignited the Australia order in the early 21st century.

The important thing for coaches, however, is to let natural flair flourish if it exists. Writing 40 years ago, Don Bradman, who claimed not to have been formally coached, said: "A coach who suppresses

natural instincts may find that he has lifted a poor player to a mediocre one but has reduced a potential genius to the rank and file."

It echoed an earlier sentiment of Wilfred Rhodes, the Yorkshire and England batsman who developed his skill so well that he went from being a tailender to opening the batting. "Tha knows one thing I learned about cricket," Rhodes said. "Tha can't put in what God left out. Tha sees two kinds of cricketers, them that uses a bat as if they are shovelling muck and them that plays proper, and like as not God showed both of 'em how to play."

|

The scoop that shook the world: Misbah-ul-Haq with the shot that sealed the inaugural World Twenty20

© Getty Images

|

|

Appropriately prescient word that: shovel. For the shovel is another stroke that has entered the modern batsman's arsenal. When Robert Key faced his first ball of this season's Twenty20 Cup,

from Robin Martin-Jenkins at Canterbury, the Kent captain had no thought of circumspection or seeing what the wicket would do; he knelt down and flicked the ball over the wicketkeeper's head for four.

Key was following in a line of modern shovellers such as Moin Khan, Doug Marillier, and Mohammad Ashraful, who used it to such good effect against Australia in 2005, but the idea is believed to have developed almost 100 years earlier when an Australia Test wicketkeeper named Sammy Carter used the stroke to hoick balls over his left shoulder.

The advantage of the shovel is that it uses the pace that the bowler puts on the ball, so all the batsman needs to do is get enough of the face of his bat on the ball to fox the fielders. The disadvantage, as Houghton says, is when it goes wrong. "You need a high level of skill and courage to get down on one knee and play the shovel when the ball is being bowled at 85mph," he says. "Mal Loye plays that stroke particularly well. It used to be used to defeat fields at the end of an

innings but now it is used from the start."

Arguably a mis-hit shovel led to the creation of the Indian Premier League and the recent rush of money into the game. Had Misbah-ul-Haq, with six needed off four balls to win the first World Twenty20 final against India, not tried to shovel away Joginder Sharma, only to be caught by Sreesanth at short fine leg, Pakistan would probably have won. And would India have had such fervour for Twenty20?

Reversal misfortune

It was another mis-hit moment of over-elaboration 20 years earlier that turned a global final away from England. At Eden Gardens, Calcutta, England finally looked as if they might win the World Cup when they reached 135 for 2, chasing Australia's 253. Mike Gatting was well set when Allan Border decided it was time to try something different. Border was not unknown as a left-arm orthodox spinner but it was getting towards Hail-Mary time. Gatting could have played his first

ball with caution but for some reason a fuse went in his brain and, bending down, he tried to play a reverse-sweep. Sadly for Gatting and England, the ball ballooned up off his shoulder and a surprised

keeper, Greg Dyer, caught it.

| |

|

|

|

| |

| The reverse-sweep re-emerged in the 1980s, and post-Gatting got some form of rehabilitation among the more innovative one-day sides of the 1990s, who saw it as a means of unsettling leg-heavy fields |

| |

Gatting, 20 years on, maintains it was the right shot to play. "I knew where he was going to bowl and he knew that I knew," Gatting says, pointing out that England's policy of sweeping and reverse

sweeping had worked in the semi-final against India. "If I had left it, the ball would have been a wide by a long way. Instead it was so wide that I tried to fetch it with the reverse-sweep, but instead of clearing my arm it clipped my shoulder and lobbed up to the keeper. We never recovered but I don't regret the shot."

Two years earlier, after watching Ian Botham make a mess of the same stroke, Peter May, the chairman of selectors at the time, banned England from using it. "I have thumbed through the MCC

coaching manual and found that no such stroke exists," May said. David Lloyd, not normally a po-faced traditionalist, also decries the reverse-sweep. "It's like Manchester United getting a penalty and

Bryan Robson taking it with his head," Lloyd said.

As with most of the unorthodox strokes mentioned, the reverse sweep appears to have been tried some time earlier. Duleepsinhji, nephew of Ranji, was said to have played a wide off-side ball "backwards towards third man with his bat turned and facing the wicketkeeper" in a match in the 1920s. The fielders appealed, unsuccessfully, for unfair play.

It re-emerged in the 1980s, and post-Gatting got some form of rehabilitation among the more innovative one-day sides of the 1990s, who saw it as a means of unsettling leg-heavy fields. Dermot Reeve's Warwickshire were particularly keen on it. Mind you, they also tried deliberately throwing down the bat when facing spin bowlers as a means of not getting an edge. That was ruled beyond the pale and not even Pietersen could attempt the same and hope to get away with it.

Patrick Kidd is a staff writer on the Times and the author of the cricket blog

Line and Length (www.timesonline.co.uk/lineandlength)