Pushing the laws to the limit

Incidents that got the lawmakers thinking

| ||

Until 1889 there was no mechanism whereby an innings could be declared, and sides had to bat on until their last wicket fell. This led to some farcical incidents, best highlighted by a game between Surrey and Sussex in 1887. Surrey had a big lead and wanted a go at Sussex on a deteriorating pitch, but Sussex were equally keen not to have to bat. Thomas Bowley tried to get stumped but the wicketkeeper refused, and then Sussex prolonged the innings by sending down a raft of no-balls. Eventually, Bowley kicked down his stumps but enough time had been lost to allow Sussex to escape with a draw. Surrey, learning from this, gave away wickets against Nottinghamshire later that summer, causing much anger among the Trent Bridge crowd.

Verdict Questionable

Outcome Law changed

Gentlemen prefer blondes, apparently. Back in the 1890s they also preferred to score their runs on the off side. Leg-stump half-volleys were routinely patted back to the bowler ("try again, old bean"), and it wasn't until an Indian prince descended on the English game that a whole new zone of scoring was opened up to cricket. Having been taught by his coach to anchor his back foot in the crease to keep him in line against quick bowling, Ranjitsinhji discovered that he could use his wonderfully supple wrists to flick the straighter deliveries off his hips to the fine-leg boundary. Not everyone was taken with this tactic however - it was deemed immoral by some, although that might have stemmed more from the racist hostility that Ranji attracted from some of the more reactionary types at the MCC. But Neville Cardus described his strokes as "lovely magic", and by the time he'd played 15 Tests for England, averaging 44.95 with two hundreds, the Victorian public had been won over as well.

Verdict Innovative

Outcome Became part of the game

Under the rules of the day, bowlers were allowed to send down looseners at any time, and in the Ashes Test at The Oval in August 1909, Warwick Armstrong, a player always willing to stretch the laws to their limit, spent almost 15 minutes bowling a succession of warm-up deliveries to one side of the pitch while Frank Woolley, making his debut for England, stood waiting to face his first ball. The crowd booed as the ball was allowed to trundle to the boundary and the Australian fielders showed little hurry in returning it, but there was nothing the officials could do. Eventually Armstrong resumed playing and, unsurprisingly, Woolley was soon out for 8.

Verdict Against the spirit

Outcome Laws changed

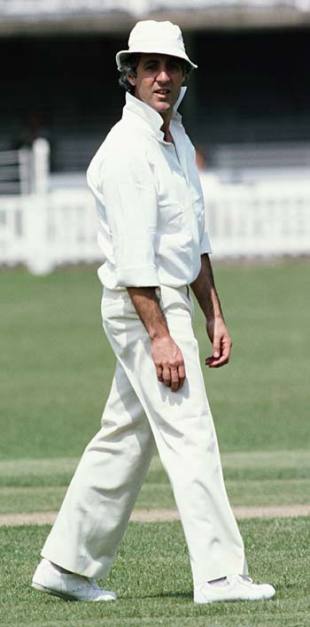

| ||

Mike Brearley's captaincy has achieved a nearly divine reputation, and there is no questioning his readiness to innovate. On the last day of a county game at Lord's in 1979, he was struggling to get wickets against a Yorkshire side who, he recalled, "were batting without much sense of adventure". He consulted slow left-armer Phil Edmonds and then picked up the spare helmet from behind the wicketkeeper and plopped it down at short midwicket. The aim, he said, was to encourage the batsman to hit against the spin in a bid to earn an easy five penalty runs. The ploy failed and in the revised laws published later that year it was decreed where the helmet could and could not be placed.

Verdict Innovative

Outcome Laws changed

Most debates about the legality of a tactic or new innovation stay within the confines of the sport. But Bodyline ended up in the corridors of power in both British and Australian governments, threatening a diplomatic incident and souring relationships between both sides. The actual incidents are well known, the key point being Douglas Jardine's instructions to his quick bowlers to aim specifically at the body and head of the batsmen from round the wicket, with a packed leg-side field, therefore making scoring virtually impossible. The Australian Cricket Broad (ACB) sent a telegram to the MCC. "Bodyline bowling has assumed such proportions as to menace the best interests of the game, making protection of the body by the batsmen the main consideration," they said. "This is causing intensely bitter feeling between the players, as well as injury. In our opinion it is unsportsmanlike. Unless stopped at once it is likely to upset the friendly relations existing between Australia and England." The tour continued - the ACB realising cancellation would have a serious financial impact - but the fallout lasted well beyond the conclusion of the trip. At the end of the season the MCC passed a resolution to say that "any form of bowling which is obviously a direct attack by the bowler upon the batsman would be an offence against the spirit of the game" and in 1934 added a clause to the law restricting the number of fielders behind square on the leg side.

Verdict Innovative

Outcome Law changed

Another controversy to spring up in Australia, this time during India's 1947-48 tour, when Vinoo Mankad ran out Bill Brown while in the action of delivering the ball in Sydney. It wasn't the first time Mankad had courted controversy in this way, having earlier run out Brown during a tour match. It led to the term "Mankading" to describe the dismissal of a batsman in such circumstances. For a long time it was left the spirit of the game to determine the outcome, with the presumption that the batsmen would first get a warning. However, it didn't stop bowlers taking advantage and it was happening as recently as the early 1990s, when Peter Kirsten was run out by Kapil Dev at Port Elizabeth. The laws have since been changed so that a bowler cannot perform a run out once he has begun his delivery stride.

Verdict Against the spirit

Outcome Law changed

The nadir of over-rates probably came in the 1970s and 80s with the four-prong West Indies attack, but the problem hit the headlines in 1954-55 when England captain Len Hutton ordered his bowlers to take their time, in order to give their team-mates time to recharge their batteries and to frustrate the batsmen. Alec Bedser recalled that he was ticked off by Hutton for getting through his overs too quickly. Various remedies have been tried, mainly ineffective financial penalties, and more recently captains have even been banned for not ensuring their bowlers get through overs quickly. What is sure is that the pre-war days of 20-plus overs an hour are long gone, and 14 is the acceptable norm.

Verdict Gamesmanship and idleness

Outcome It rumbles on ... and on

| ||

There have been some short one-day games in history, but the encounter between Somerset and Worcestershire at New Road, during the Benson & Hedges Cup, took it to extremes. And it was nothing to do with the amazing skill of a bowler. Rose, the Somerset captain, realised that his team would qualify for the next round as long as they weren't overtaken on strike-rate - an old formula for splitting teams level on points, rather than today's net run-rate - and so took the rules of the competition to the extreme. At the time there was nothing to say a side couldn't declare, and after one over of Somerset's innings Rose called his team in at 1 for 0. It meant they would lose the game, but the target was so small that it wouldn't damage Somerset's strike rate. Worcestershire knocked off the runs in ten balls, leaving the good-sized crowed nonplussed, and the repercussions soon started. "I had no alternative," Rose said. "The rules are laid down in black and white. If anybody wishes to complain, they should do it to the people who make them." And the England board did act. An emergency meeting was called and Somerset expelled; the laws were changed soon after to prevent declarations in one-day cricket.

Verdict Against the spirit

Outcome Law changed

Possibly the most flagrant example of rule-bending that the game has ever seen. The third final of the B&H World Series at Melbourne in 1981 had come down to the last ball, and New Zealand's Brian McKechnie needed six runs to secure a tie. It wasn't a prospect that Australia's captain, Greg Chappell, was prepared to entertain, and so - to the horror of the crowd, commentators and several team-mates, including the wicketkeeper, Rod Marsh - he instructed his brother Trevor to roll the ball underarm along the ground. McKechnie blocked the ball then threw his bat away in disgust, as New Zealand's captain, Geoff Howarth, rushed onto the field to remonstrate with the umpires. Richie Benaud, pulling no punches, described it as "the most disgraceful moment in the history of cricket", adding that it happened only because Chappell got his sums wrong. Dennis Lillee should have been entrusted with the key over, but he had been recalled to the attack an over too soon. Robert Muldoon, New Zealand's prime minister, called the delivery "an act of cowardice", adding that it was appropriate that Australia had been playing the match in yellow.

Verdict Against the spirit

Outcome Law changed

Dermot Reeve was never shy of trying something different to annoy the opposition and his captaincy was a key to Warwickshire's success in the 1990s. But when he started to throw his bat to the ground against Hampshire, it ruffled more than the usual number of feathers. Raj Maru, the left-arm spinner, was bowling over the wicket into the rough and Reeve was trying to pad him away. To avoid the risk of being caught bat-pad, Reeve dropped his bat on 15 occasions during 28 overs at the crease. "I saw John Emburey do it some years ago against Norman Gifford after he had almost been caught off the glove," Reeve said. "The next ball he simply dropped the bat. I've seen too many batsmen out because the ball has bounced off the pad onto the bat or glove, and if you drop the bat that cannot happen."

Verdict Innovative

Outcome Law changed

"We flippin' murdered 'em," was the famous verdict of England's coach, David Lloyd, after the first Test against Zimbabwe at Bulawayo in 1996-97 had finished, uniquely, as a draw with the scores tied. But that was only half the story. England were in the midst of the tour from hell - they had lost to Mashonaland and been routed in the first ODI - and they desperately needed a victory to get the travelling press off their backs. Their opportunity came when they were set 205 in 37 overs in the fourth innings, which boiled down to 13 off the final over, bowled by Heath Streak. A vast six from Nick Knight reduced the requirement to five from three, at which point Streak decided to bowl as wide as he could down both sides of the pitch. Knight, who batted heroically for 96 not out, could manage only two runs from the final ball, as Darren Gough was run out going for the match-winning third. "When you're trying to save a Test match, you use every trick in the book," said Zimbabwe's captain, Alistair Campbell. "Other sides have done it, and I'll defend it to the hilt."

Verdict Tactical

Outcome Can still be done, although the wide law has been tightened

Martin Williamson is Executive Editor, Andrew Miller UK Editor and Andrew McGlashan a staff writer of Cricinfo