The Kingston Test in 1968 is best remembered for the ill-advised use of tear gas by the police to control the crowd. Geoff Smith, the Jamaican Broadcasting Corporation scorer at the game, looks back

|

|

|

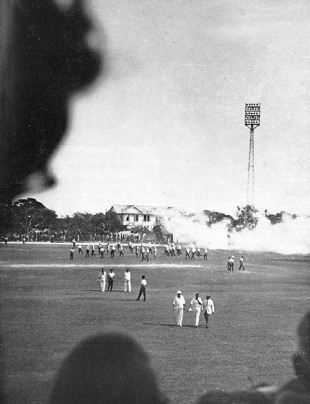

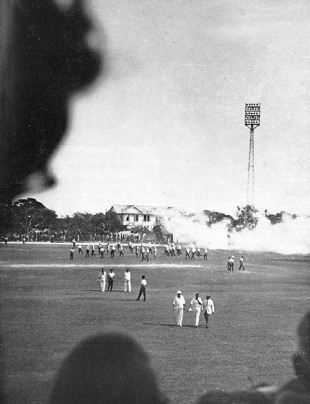

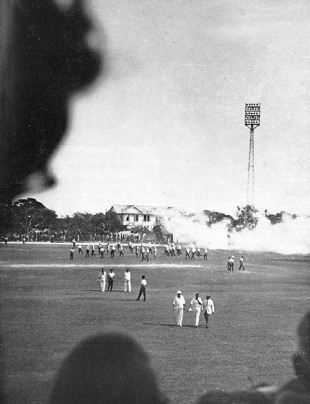

Confusion as the tear gas fired by the police heads away from the crowd and towards the pavilion where players and board officials were sitting

© Cricinfo

|

|

| |

John Thicknesse's memorable headline lives forever. Describing play on the fourth day of the

second Test between West Indies and England, EW Swanton confessed in the

Daily Telegraph: "Typing this with more than a whiff of tear gas making things unpleasant in the press box, one is confused by events ..."

The trigger had come a few minutes earlier, when Basil Butcher had been caught left-handed, low down behind the wicket by Jim Parks off Basil D'Oliveira's bowling from the north end of the ground. Neither Barbadian umpire Cortez Jordan at square leg nor standing umpire, Douglas Sang-Hue from Jamaica, needed to signal: Butcher walked immediately when he saw his leg glance fail.

Sabina Park is a small, dedicated cricket ground. The elliptical arena has a raised north-south wicket with short boundaries behind the bowlers. The Jamaican Broadcasting Corporation (JBC) radio commentary team occupied a box directly behind the wicket, three storeys above ground. Above the commentary booth was a covered platform for newsreel cameramen.

The JBC's commentary position was a shoe-box. At the front desk sat the revered, burly, Jamaican broadcaster Roy Lawrence. Match expert Jackie Hendricks, the former West Indies and Jamaica wicketkeeper, sat on his right. As JBC's scorer, I sat to Roy's left. The side wall was plastered with sheets of cricket data. George Baker, the JBC radio engineer, monitored proceedings from the rear. Behind those seated stood the BBC's Brian Johnston, waiting go on air.

The Conditioned Air Corporation (CAC) had fitted external cooling units to serve the radio teams and the press box adjacent, all on the unofficial understanding that Roy would make occasional mention of CAC.

Before David Holford joined Garry Sobers at the wicket, one or two bottles and catering trash had been thrown from the area of the scoreboard, in the direction of John Snow at third man. Much abuse was shouted at the batsmen as West Indies, who were following on, were still 25 runs in arrears.

This encouraged the crowd in the south-east bleachers to throw bottles and bric-a-brac. Until then it had been a calm sea of spectators sporting red, white and blue foldout caps advertising Pepsi-Cola, the dominant local soft drink.

Not unknown for his belligerence, Snow advanced towards the crowd appealing for calm. Instead a greater storm of debris rained down. Colin Cowdrey, England's captain, strode over in an attempt to placate spectators. Sobers, too, walked over to appeal for calm.

But as it seemed that they had quelled the trouble, matters were taken out of their hands by the local police who hustled across the playing area to confront the malcontents. Almost immediately they were followed by the police's mobile reserve wearing white riot helmets and waving long truncheons. These moves proved ineffectual.

Much cussing - a local term for good-tempered, vocal abuse - developed, encouraging spectators in the South Camp Road bleachers to join in. Bottles rained down on the field of play.

The prevailing winds come off the sea in the south-east quarter. At 35mph they eased the ground temperature of 115 degrees, making it a pleasant 80-degree afternoon under cloudless skies. An order was given for tear gas to be fired into the crowd in the south east bleachers.

This caused the crowd to disperse quickly, some incurring minor injuries in the scramble, but the bulk of the gas from ten or so canisters was blown back into the police. Some of the gas was drawn by the air conditioning units into the media area. "Most unpleasant", Swanton reported.

The bulk of the gas reformed as a pale grey cloud about 20 feet high by 60 wide and blew across the ground into the main pavilion. On the first-floor balcony, the governor general, Clifford Campbell, sat in regal splendour with members of the government and the West Indies board. This group was affected worst by the tear gas. Although discomforted ourselves as we recovered from a dose of tear gas in the scoring tower, the plight of the dignitaries and their guests taking the brunt of the gas raised a smile. The cloud eventually petered out over the adjoining St. Joseph's Academy.

|

|

|

Colin Cowdrey appeals to the spectators

© Cricinfo

|

|

| |

Meantime, the crowd had overwhelmed the boundary fences and had surged onto the playing area. As the police and the players retreated to the pavilion, the pitch was overrun. After an hour of discussion, a resumption of play was announced for 4pm over the public address system. When the game did restart, one minor disturbance occurred in a stand, which was settled quickly from within the crowd.

The extra 70 minutes on the sixth day, agreed to make up lost time, almost proved disastrous for England. From being beaten and facing defeat at 204 for 5 after five hours of struggle, West Indies batted on for a further six hours into the fifth day.

The pitch had dried out and cracked, so much so that Jeff Jones made the ball deviate wildly when he hit one of the cracks. Sobers declared to let his bowlers have a go, and the tactic almost paid off. By the close, England were 19 for 4 and could well have done without the added time.

The drama wasn't finished. Play resumed at 10am and wickets continued to tumble. When David Brown was out with the score at 68 for 8, D'Oliveira was the only one on the ground who realised that 70 minutes were up at 11.10am.

With two balls of the 39th over remaining, D'Oliveira tucked his bat under his left arm, beckoned to David Brown, England's No. 10, and the pair strode off towards the pavilion leaving the umpires bemused. Once the penny had dropped, the pair pocketed the bails, withdrew the stumps and left the field with the downcast West Indies team.

Fifty minutes later, the England coach left the ground, seen off by a handful of disgruntled fans hurling abuse.

The deal reached between Cecil Marley, chairman of the West Indies board, and the tour management was for an additional 70 minutes of play and not a specified number of overs. What is more, the records have been fixed to show five balls bowled in the final over not four.

In a private conversation before he died - Marley was a builder; I was a quantity surveyor - Marley said he wished he'd stipulated a fixed number of overs. He had feared that the Test would have been abandoned, which would reflect badly on Jamaica, something unthinkable for the Jamaican government and establishment.

Was it a riot? Not really. No public order offences. No arrests. No tampering with the pitch. Panic following the discharge of tear gas shells and their detonation in an unsuspecting crowd? Most definitely.

The festival attitude of the crowd and its ready acceptance of the circumstances say more about the day than anything else. The fightback by the West Indies team and their near victory over England was its own reward for the 15,000 or so in Sabina Park.