|

|

|

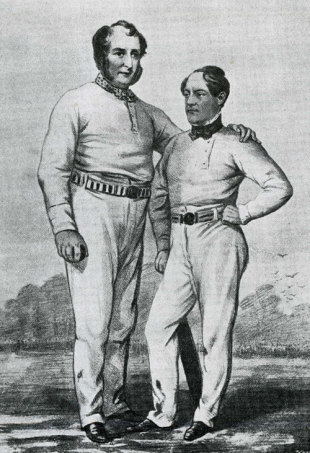

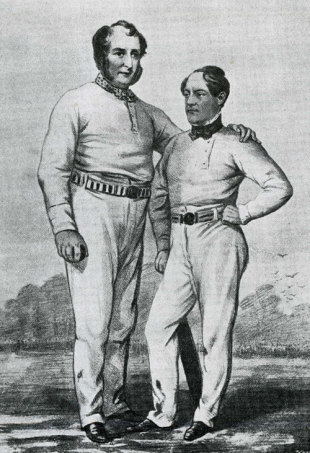

Alfred Mynn and his old friend Nicholas Felix

© Cricinfo

|

|

| |

In the 19th century, single-wicket contests were extremely popular, pitting, as they did, the great cricketers of the era against each other head-to-head. Other combinations - two v two or even handicaps, with two v four - were also regular features of the calendar.

The rules of those contests are unfamiliar to the modern cricket watcher. For single-wicket games, the number of fielders was limited, usually to five or less; runs could only be scored in front of the wicket; to score a run the batsman had to get to the bowler's end and back; a batsman could not leave his crease before making a stroke; in some games batsmen could not be caught behind or stumped. In general, rules were agreed on a match-by-match basis even though they were officially drawn up in 1831.

Social conditions made games of this sort popular: before the arrival of a national railway network in the 1840s and 1850s, it was easier to get two top players to a ground than 22 of them. The games were often slow, with the bowler allowed up to a minute between deliveries. In lengthy contests, exhaustion was a real possibility. What's more, with runs hard to come by because of the strict rules, long periods with no scoring were common.

In 1833, Tom Marsden and Fuller Pilch met in two matches for the Championship of England. Pilch, who expressed no enthusiasm for single-wicket games, won easily. Five years later, another Championship of England was staged, in which Alfred Mynn beat James Dearman.

In 1846 the third, and greatest, contest for the Championship of England took place. Mynn, who at the time was the undisputed leading player in the land, was challenged to play Nicholas Felix, a very good cricketer himself. The two were old friends but cut contrasting figures. Mynn, about 114kg, but muscular and tremendously fit, against Felix, described as resembling a cerebral head teacher.

On June 18, 1846, the pair met at Lord's. On paper, it was not a contest. Although the 41-year-old Felix could bat, he favoured shots behind the wicket, which were not allowed in the single-wicket format. More crucially, he was no bowler, and his lobs rarely saw the light of day - in his career he took nine first-class wickets. Mynn, two years younger, bowled fast and hit the ball hard and appeared perfectly suited to this version of the game. As was the norm then, the gamblers were out in force and the winner was also assured £200.

Felix batted first but struggled to score against Mynn, who, like his opponent, was supported by two fielders. Mynn's pace can be gauged by the fact that he splintered Felix's bat (which in those days would not have been sprung), and with the next delivery bowled him for 0.

Mynn started boldly but when he had made 5 he was brilliantly caught and bowled. "It came to me like a cannon shot," Felix admitted. "I only had time to put up my hand to save my life."

The second innings was attritional. Mynn hurled down 247 balls, of which Felix hit 175. But despite that, he only managed three runs as a majority of his strokes finished behind the wicket, and added to that was one wide. Eventually, Mynn broke through Felix's defences and bowled him. Mynn had won by an innings and one run.

In more than five hours, eight runs had been scored off the bat. But far from being bored senseless, the crowd was reportedly enthralled by the contest. There was so much interest in the showdown that a return match was hastily arranged.

It took place in Bromley on September 29. Marquees were erected to cope with the huge crowds that flocked to the ground. The outcome was the same, but once more Felix proved a tough obstacle. In all, he scored 12, but ten of those were wides and one was a no-ball. Mynn won in his second innings. He never lost a single-wicket contest in his career.

It was the last of the great single-wicket contests. There were more games, but often they were staged at the end of other standard matches, and by the 1870s they had all but died out.

A month before the Bromley match, William Clarke had set up his travelling All England XI, and the explosive growth of the railway meant that the public taste switched to watching the best cricketers in the land take on local sides. Both Mynn and Felix, although nominally amateurs, were involved in Clarke's venture from the off.

Bibliography

A Social History of English Cricket by Derek Birley (Aurum, 1999)

More Than A Game by John Major (Harper Collins, 2007)

Is there an incident from the past you would like to know more about? Email us with your comments and suggestions. Martin Williamson is executive editor of Cricinfo