|

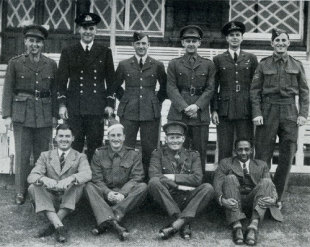

Learie Constantine in the nets at Lord's at the start of West Indies' 1939 tour of England

© Martin Williamson

|

|

Learie Constantine was one of the greatest cricketers to come from the West Indies and also a tremendous ambassador for the region. Through the 1930s he played in the Lancashire leagues, establishing a home in Nelson, and he remained in England when the war started, raising funds and working for the Ministry of Labour in Liverpool where he acted as a welfare officer, coordinating with West Indian technicians and trainees on Merseyside.

One of his duties was to arrange fund-raising matches. He was to play in two such games at the end of July 1943 and he was given four days leave. On July 30 Constantine travelled to London with his wife and daughter to play some charity matches at Lord's and Guildford.

Constantine had booked two rooms at the Imperial Hotel in Russell Square in advance, and when making arrangements had taken the precaution of asking if his colour would cause any problems and was assured it would not. Racial slurs were, he recalled, "an unpleasant part of living in Britain."

When Constantine arrived with his family on the evening of July 30 it was immediately apparent that they were not welcome and after a brusque exchange with Margaret O'Sullivan, the manageress, asked to see the hotel manager. "You can stop tonight but not any longer," the manager told him. When Constantine replied that he had booked for four days, the manager said: "You can go when you like ... I can turn you out when you like."

At that point Arnold Watson, Constantine's boss at the Ministry of Labour, arrived and seeing Constantine and his wife distressed, asked what was happening. "We are not going to have these niggers in our hotel," the manageress told him. "He can stay tonight but he has to leave tomorrow morning and if he doesn't his luggage will be put outside and his door locked."

Watson was flabbergasted. "You can't turn Mr Constantine and his party out like this," he said. "We won't have niggers in this hotel," O'Sullivan repeated. When asked why not, she replied: "Because of the Americans," a reference to the number of US citizens staying there who, the implication was, would take offence to his colour. She later said that she feared a quarrel between Constantine "and the Americans and colonials" and that she had "no staff to quell it".

Watson curtly pointed out that Constantine was a British subject and a government employee, but it cut no ice. "He is a nigger," O'Sullivan repeated.

Faced with a situation fast getting out of hand, Watson persuaded Constantine to leave and accept the offer of a room in the nearby Bedford Hotel, which was run by the same management. He later recalled they were treated very well there.

In an era when racism was widespread and not illegal, that might have been the end of it. But Constantine was not the kind of man to be bowed. As a cricketer, he said, he was a figure of status, but as a human being and citizen he could be denied a bed in a city where he had come to play.

He played for a British Empire XI against Guildford on August 1, taking 7 for 37 in front of a large crowd, and then at Lord's where 40,000 turned out over two days to watch a Dominions XI play an England XI.

Constantine, meantime, decided enough was enough. "The time has come," he said, "to take to the courts." He also had some high-level backing. A top barrister, Sir Patrick Hastings, was hired for what was seen as a test case whose outcome could influence the attitude of West Indians to the war effort.

The incident became public knowledge on September 22 when it was raised in the House of Commons where several MPs asked the Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison, to comment. Morrison explained that as Constantine had by then decided to sue the hotel he could not comment on specifics, but he added that he believed there was "a responsibility on all members of the community to avoid discrimination against any British subject on grounds of race or colour."

|

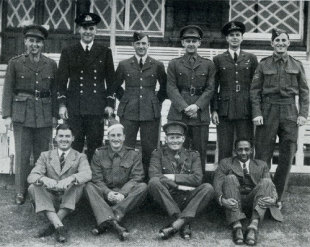

Constantine at Lord's in 1940 for a charity match

© Martin Williamson

|

|

In June 1944 Constantine's claim that Imperial Hotel had "refused to receive and lodge him" was heard in the High Court. The evidence took two days, and in defence, the hotel's managing director denied that any racists terms had been used in conversations. After a weekend's deliberation, Justice Birkett decided in favour of Constantine, rejecting the evidence of the defence and adding that he was convinced that O'Sullivan had used "deeply offensive" language. Constantine, he continued, "bore himself with modesty and dignity, dealt with all questions with intelligence and truce truth, and was not concerned with being malicious or vindictive."

However, although the prosecution asked for exemplary damages, Birkett explained he was not able to do so and awarded Constantine five guineas in damages, not for the racism but for the fact he was unlawfully denied accommodation when it was available and he was willing to pay.

"Had I been inclined to do so, I could probably have succeeded in a further action for defamation," he wrote. "But I was content to have drawn the particular nature of the affront before the wider judgment of the British public in the hope that its sense of fair play might help protect the people of my colour in England in future. From the tone of the hundreds of letters of congratulation I received from all over the country, I think my object was attained."

Bibliography

Learie Constantine by Gerald Howat (Allen & Unwin, 1977)

Is there an incident from the past you would like to know more about? Email us with your comments and suggestions. Martin Williamson is executive editor of Cricinfo