|

Little cricket, lots of corruption

The game was an afterthought in a decade of near anarchy under the Mugabe regime: Zimbabwe lost Test status, most of its senior players, and the compassion of the cricketing world

|

|||

|

Related Links

Feature : Bleaker than ever

News : A few sparks amid the gloom In Focus:

The Zimbabwe crisis

Teams:

Zimbabwe

|

|||

At the start of the millennium, few had any idea what a tumultuous decade was in store not only for Zimbabwean cricket but for the country itself. As we now know, a place heralded as one of Africa's success stories descended into near anarchy under the brutal regime of Robert Mugabe, and unavoidably cricket was dragged down with it. At times it was hard to see how cricket could survive in such a dysfunctional society, but it managed, often against all the odds, and is still just about keeping its head above water.

A review of the last 10 years is more of a political essay than a cricketing one. Too often, the game itself was almost an afterthought - a situation made worse by the overt politicisation of the board in the middle of the decade. Stories about cricket in Zimbabwe were inevitably centred on the mess inside the country and debate over the morality of maintaining cricketing links with them.

The international community was divided. Unfortunately the countries that adopted the hardest line towards Zimbabwe were predominately white, allowing Mugabe to play his race card. In the smaller cricketing world, the governments of the UK, Australia and New Zealand fought a determined battle to sever ties with Zimbabwe until such time a degree of normality returned. To their shame, the cricket boards of those three adopted an often cowardly attitude, with money being put before anything else, including their own players, who were too often left alone to make career-affecting decisions with little or no guidance.

As 2000 dawned the future looked rosy for the Zimbabwe side. It had a team with a wealth of experience, and a batting line-up that was able to hold its own with any country. World Cup wins over India and South Africa in 1999 had further boosted the profile of the game, and the year ended with a defeat of Sri Lanka in an ODI at Harare Sports Club.

Progress continued in the early part of the decade, although to those who cared to look beneath the surface, the country itself was beginning to unravel as Mugabe sought to paper over his appalling mismanagement with increasingly desperate legislation. Spectators who tried to use matches to highlight the failing society were brutally dealt with. In 2002 one was killed after unveiling an anti-Mugabe banner at a Pakistan ODI in Bulawayo.

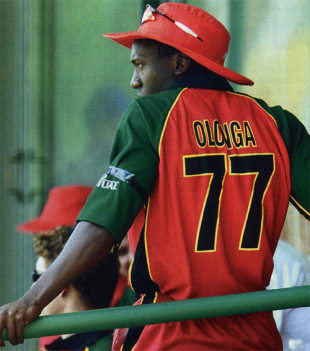

The watershed came at the 2003 World Cup, an event that should have been a showcase for southern African cricket but which lurched from one mess to another. All that was wrong with Zimbabwean society was brought to a wider audience by the famous black-armband protest by Andy Flower and Henry Olonga during a group match in Harare. The board, by now increasingly in line with the thinking of those ruling the country, tried to stifle the pair but the cat was out of the bag and all it managed to do was make things worse.

By the end of the tournament Zimbabwe were clearly a divided side, and just how much so became clear a year later, when a clumsy attempt to replace Heath Streak as captain rapidly became a much more serious matter after the bulk of the country's (predominantly white) team walked out in support of their skipper. From then on, the game stumbled from crisis to crisis, almost all avoidable but somehow inevitable.

The one constant throughout the decade - and of the one before it - was board chairman Peter Chingoka. From one of Zimbabwe's wealthier families, he was originally seen as a careful and canny safe pair of hands and a man who guided Zimbabwe through its difficult early days as a Full Member of the ICC. But as the country became increasingly politicised, so did Chingoka. His denials of links to the Mugabe regime may have convinced many internationally that he was an innocent caught up in events, but those inside the country were not as easily fooled. They pointed out that to survive under Mugabe you needed to toe the party line.

| The ineffectiveness of the ICC was almost a constant in Zimbabwe's decline. Fact-finding missions were shown what the authorities wanted them to see, and too often the word of Chingoka and others was taken as gospel. Those opposing the board were blithely dismissed as rabble rousers, despite often having served the game loyally for decades | |||

Eventually it took the actions of politicians to unmask Chingoka, and he was banned from first the European Union and then Australia and New Zealand because of his links to Mugabe. Even then the ICC feebly pretended it was not its responsibility to delve deeper. Two cricketers wearing black armbands produced an official censure, but a man closely linked to a despot was repeatedly welcomed with open arms at the ICC's top table.

The ineffectiveness of the ICC was almost a constant in Zimbabwe's decline. Fact-finding missions were shown what the authorities wanted them to see, and too often the word of Chingoka and others was taken as gospel. Those opposing the board were blithely dismissed as rabble-rousers, despite often having served the game loyally for decades.

There was perhaps a brief opportunity in May 2004 for the ICC to have made a difference, although given all that was happening on the wider political front in Zimbabwe the chances were slim. Instead it proved typically supine, even allowing Malcolm Speed, its chief executive, to be humiliatingly snubbed by Chingoka when Speed flew to Harare to try and help find a way out of a rapidly escalating shambles. He was left to amble round a park in Harare while a board meeting took place behind closed doors.

Those running the ICC maintained it was powerless to act, and that allowed Chingoka and others to banish anyone opposing them, hand-pick stooges to run local boards, redraft the constitution to make their removal all but impossible, and eliminate the flickering remnants of any credible alternative.

If the ICC was all too willing to dismiss the politicisation of Zimbabwean cricket, what it could not ignore was the plummeting standards of the cricket itself. In 2004, Zimbabwe suspended itself from Test cricket for a year after two massive innings defeats against Sri Lanka. It returned nine months later, only to suffer eight more humiliations before a second suspension. Officially this was at Zimbabwe's behest, but few believed that. They continued to play ODIs but the results were equally dispiriting. In the period from the sacking of Streak through to the end of 2009, only 26 matches were won out of 111 played, and aside from Bangladesh only one of those wins came against a Full Member (West Indies in 2007). Even a memorable victory over Australia at the inaugural World Twenty20 in the same year could not disguise how far the side had fallen.

Inside Zimbabwe the mess was, if anything, even greater. Domestic competitions lurched from one calamity to another, and at one stage there was not even enough wherewithal to host the Logan Cup, the century-old first-class domestic tournament. As the economy went into meltdown, equipment became scarce, facilities deteriorated, and any cricket that was played was often of a very poor standard.

By 2008 it appeared things could not get any worse. Questions, however, began to be asked about the board's finances as the ICC continued to pour in millions of dollars. An audit arranged by Chingoka with a tiny Harare-based accountant convinced nobody, and eventually the ICC decided on a specially commissioned independent forensic audit. After a series of unexplained delays, the report was produced but the ICC refused to make it public. Only a few blinkered souls in Dubai appeared to not see how ludicrous that decision made all those involved look.

But as the decade neared an end there was finally progress. Julian Hunte, the head of a West Indies board almost as dysfunctional as the one he was asked to investigate, produced a report on the state of the game in Zimbabwe and slowly change began to be seen. The domestic structure was overhauled and made more transparent. Former players were wooed back into the fold, and even the media, for so long seen as an enemy to bash or manipulate, was subjected to a charm offensive.

|

|||

|

|

|||

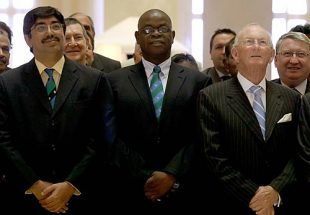

At the forefront of this change of tack was Ozias Bvute, a controversial figure who was at the heart of many of the rows in 2003 and 2004. Portrayed then as the antichrist, in the last year he has been more Ban Ki-moon. The reality is probably somewhere in between, but by focusing on the future he has managed to galvanise the board into giving the impression to those inside and outside Zimbabwe that there is hope. He, and not the increasingly marginalised Chingoka, is instrumental to the rebuilding of Zimbabwean cricket.

There is a long way to go. Six or seven years of neglect cannot be overturned overnight, and the crumbling structure of school and club cricket remains in need of urgent attention. The national team are still international cricket's whipping boys, and despite no end of verbal support, even those countries with governments ambivalent to Mugabe remain reluctant to play matches against such a poor and commercially unappealing opponent.

The next two or three years will decide if cricket is to survive in any meaningful way inside Zimbabwe. If the advances made in 2009 can be built on then there is hope. But the very thing that started the rot, the eccentricities of the country's leading political elite, will ultimately decide which direction things will go. If Zimbabwe can sort itself out and move ahead, then cricket should be strong enough to follow. It remains a huge if.

Martin Williamson is executive editor of Cricinfo and managing editor of ESPN Digital Media in Europe, the Middle East and Africa

© ESPN EMEA Ltd.

| ||||||

| Comments have now been closed for this article |

||||||

- From Launceston to the top of the world

- A video look back at Ricky Ponting in the 2000s

- Ponting voted Player of the Decade

- Australian captain beats Jacques Kallis to be voted cricketer of the 2000s

- 'This one's extra satisfying' - Ponting

- Cricinfo's Player of the Decade title is "a great honour and a great thrill" for Australia's captain

- Laughing boy

- Like Bradman before him, Ponting turned the opposition into ball-ferriers, delighting in his mastery all the while

- Gilly and Baz go bonkers

- Flintoff's Edgbaston magic, a Tendulkar gem, that 434 chase, and the IPL's fiery start feature in the second part of our performances of the decade

- Stoinis 'absolutely fine' with not getting a CA contract, still keen to play for Australia

- Marcus Stoinis silences Chepauk with hundred in record chase

- Gaikwad: 'Dew took our spinners out of the game'

- Hayley Matthews' 141 completes ODI series sweep for West Indies

- Rashid: 'Things change quickly... we have the mindset of champions'

All there is to do is keep optimism in mind and hope that the progress made continues to flourish and the country can politically develop. The more the likes of G.Flower, Goodwin, Rogers, Gripper, Ebrahim etc are welcomed back to the fold the more the situation will improve. They already have positive developments with the head coaching role coming along also assistance from CSA and their plans for the future including Test readmission and the domestic structure now back on its feet. In regards to the players its all well and good, the likes of Price, Taylor, Vermuelen, Cremer, Williams, Mazakadza and the likes there is no shortage of talent, retaining these guys as well as Goodwin, Rogers, Gripper, Ebrahim etc returning its just a matter of time before the side can stick together and take it to the Full Members. In relation to the future Test plans with CSA surely no one can see anything wrong with readmission being more than considered by the next FTP from 2012 onward.

Posted by Terry on (January 6, 2010, 3:48 GMT)Zimb players should be allowed to play test cricket (with Ireland & others). The solution is: 1. Poor Standard: Create qualification process through winning (not cricket politics) such as 2 tiers or 4 year Test World Cup (20 team group stage=>Super Eights=>Semis=>Final) to make competition for elite spots. 2. Governments: Other countries governments should have no influence in cricket. 3. Zimb Govt Influence: ICC should have stepped in if it believed Zimb Board had undue influence from the Zimb Govt. However, India, Pak & others governments have influence over their boards, as such what would undue influence be? 4. Blacks Preferred: Zimb Board should have the final say on selection. If standards fall then pt (1) should be looked at. 5. Player Exodus: ICC should have given special permission to Zimb players to represent other countries (eg: South Africa) if pt (4) was believed. 6. Finance Curruption: ICC should have examined all boards finances it provides money to & stop funding if bad