|

The screen-eyed monster

The 2000s saw cricket's television economy grow unprecedentedly and begin to dictate terms like never before

|

|||

|

Related Links

In Focus:

English television rights

| Indian television rights

|

|||

How does one measure a decade? Money would be a reasonable yardstick, especially for a sport increasingly governed by men with dollar signs in their eyes. In 1999, the BCCI signed a five-year deal with Doordarshan (DD) for the telecast of all international and domestic matches to be played in the country. In what was an extraordinarily large amount for the times, DD promised the BCCI Rs 54 crore (Rs 540 million, or roughly US$ 11.5 million at today's exchange rates) per year.

In October 2009, the BCCI announced a renewal of its four-year telecast deal with Nimbus Communications (which runs the Neo channels) for Rs 500 crore a year, or roughly US$ 110 million. Of course, this was independent of the 800-pound gorilla called the Indian Premier League. A subsidiary of the BCCI, the IPL is guaranteed roughly US$ 175 million a year for a nine-year period (2009-17) from the Sony network and its partner, the World Sports Group.

For cricket's television economy, the first decade of the 21st century has been a period of massive, unprecedented expansion. As an inflection point, it can be matched only by the early 1980s, when the Packer revolution saw coloured clothing, limited-overs cricket and, of course, Channel Nine make a deep impression in Australia. Complementarily, the 1983 World Cup and a fledgling television culture saw the beginnings of the Indian cricket boom.

Yet, nothing - not the early 1980s, not the mid-1990s, when Jagmohan Dalmiya began to monetise cricket and auction telecast rights at the BCCI and later at the ICC - compares with the past decade's frenzy. Even the 2010s may actually see a consolidation of the cricket economy rather than the sort of unreal growth figures that have been thrown around in recent years, but that's getting ahead of the story.

What has 2000-09 meant for sportscasters and what has it meant for ordinary cricket fans? The story revolves around India, the capital of the cricket economy, generating 70% of the game's revenue. It is Indian television audiences and eyeballs that determine the success or failure of a cricket tournament.

In the opening decade of the millennium, the Indian economy and television business have grown. The quantum of sports broadcasting has also increased. Newer properties have been developed. In the old days, a tennis Grand Slam semi-final would have found advertising support, but a third-round match would not necessarily have. Today, if the match in the third round features Sania Mirza it could become a significant earner. Formula 1 and the big one, the English Premier League (EPL), have become coveted properties. In fact, Indian football fans have never had it so good. They get to watch more domestic games from leading football countries than most of the planet.

However, there remain some constants. At the start of the decade, 60-65% of the revenue of ESPN-Star Sports (ESS), India's largest sportscaster network, came from cricket. While business has grown overall, says a senior ESS executive, cricket brings the same pie to the table: "about 60-65%".

What has changed is the sheer volume of cricket. "This is now a round-the-year sport," says a television executive. "Some sort of cricket, in any of the three formats, is going to be played practically every day."

Cricket's great year of change was the 12-month period following the 50-over World Cup of 2007 and culminating in the inauguration of the hugely successful IPL. Two things happened in this period. First, the world woke up to the possibilities of Twenty20. The success of the World Twenty20 in South Africa in September 2007 and India's victory there made it apparent this genie could no longer be bottled up. It was free; the IPL, as an exposition of Twenty20 and its attendant razzmatazz, was only a natural corollary.

| India's exit from the 2007 World Cup affected the way sponsors and advertisers began to look upon the business end of cricket. They now wanted a big tournament where an Indian presence was guaranteed till the very end - and so the IPL was born, as a sort of alternative to blockbuster international cricket | |||

Second, India's first-round exit from the 2007 World Cup proved a disaster for sponsors and advertisers who had contracted tournament-long deals. Investments turned to dust. Campaigns planned for the Indian viewer came to nothing because India - a country that loves its cricket stars more than it loves cricket - switched off as soon as Rahul Dravid's team took the flight back.

This affected the way sponsors and advertisers began to look upon the business end of cricket. They now wanted a big tournament where an Indian presence was guaranteed till the very end - and so the IPL was born, as a sort of alternative to blockbuster international cricket. That apart, advertisers began demanding TRP guarantees from television channels. A seller's market began to alter its basic rules.

Today, if an advertiser agrees to write a cheque to a sportscaster for a cricket series or tournament (or a set of tournaments), in some instances it only promises to pay about 30% irrespective of the TRPs. Obviously if India does well in the tournament, viewer interest rises and so do the TRPs. At this point the advertiser starts to pay more.

On their part, television channels don't want to lose money. So if the TRPs fail to rise above the agreed mark, channels still ask for the rest of the advertiser's money but promise to make up by providing more airtime for other cricket or other sports at other times in the year.

Understand the complexity of this. If an advertiser buys lots of ad spots for, say, a cricket World Cup from which India exits very quickly, resulting in TRPs collapsing, the channel could spend months undoing the damage. It would have to agree to carry ads during, for example, EPL games or the US Open tennis or the British Open golf championship. The TRPs of all these are way below those of cricket. As such, the channel could be saddled with obligatory ads for a long, long time.

The TRP-guarantee model is a critical evolution in cricket television. It is the lasting legacy of the opening decade of this century.

What did the cusp of 2007-08 mean for the television viewer? This was when, to quote an IPL franchise CEO, "cricket telecast began to be legislated far more closely in India". The BCCI - and the IPL - took charge of telecast properties. Channels lost autonomy. The BCCI would now hire a production company to produce the pictures and audio and sell these in real time to the channel that paid it (the board) the highest fee.

|

|||

|

|

|||

This convoluted model had one major implication for the viewer. It reduced if not effaced the integrity and independence of the commentator. Indeed, the decline of the commentator has been the untold but unstoppable story of the decade. From being among India's most articulate authorities on cricket, Sunil Gavaskar and Ravi Shastri have become the BCCI's in-house commentators, signed on by the board/IPL for its cricket matches.

In parallel, new forms of the game and new styles of coverage also left a shadow on the whole aura, if that is the word, of the commentator. When the decade began, Harsha Bhogle and Gavaskar, Shastri and Wasim Akram, Geoff Boycott and Tony Grieg, and even the sometimes over-the-top but outspoken Navjot Sidhu, were names. They reflected opinions that told on how you, as a viewer, saw the game.

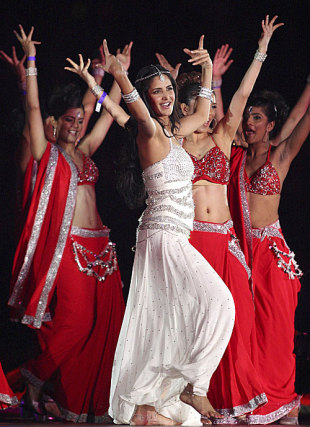

As 2009 walks back to the pavilion, it almost doesn't matter. The BCCI hires its commentators and there is a rubicon they cannot cross. For the 2003 World Cup, Sony brought in Mandira Bedi and her noodle straps, putting off some people but undoubtedly adding to the entertainment appeal of modern cricket. The IPL has taken this process to its logical extreme - when a wicket falls the television audience is more inclined to watch the cheerleaders do their number than listen to the commentator, if he has anything to say at all.

The commentator is no more placed on a pedestal as the disinterested, credible and knowledgeable observer. In effect, Indian cricket television has ensured it will never quite have a tradition of its own John Arlotts and Richie Benauds. In turn, this has impinged on the viewership and marketability of cricket features programming, as opposed to live telecast. Till even the 2003 World Cup, hour-long pre-match discussions and scenario-building sessions drew viewers and could be sold by channels as a valuable add-on to the main cricket. Interest in these has plummeted.

If this piece has emphasised the Indian experience it is because the Indian television audience is the prize every cricket authority, board, tournament organiser and network marketing chief seeks. The fact that, say, a West Indies-New Zealand Test series played in the Caribbean has any sort of global or third-party market at all for in-stadia advertising is only because some Indian couch potato may be watching and that some marketing agent may have bundled these rights with a larger package and sold them to an Indian company.

What does this signify for the rest of the cricket-playing world, and indeed for the future of the sport, at least as it appears on television? In the absence of a stake in the Indian market, foreign cricket boards are struggling.

The England Cricket Board has sold its rights to the subscription-based Sky network rather than free-to-air BBC, in a four-year £300 million deal. The consequences of Sky buying exclusive rights from the ECB have been enormous as well as enormously controversial. The pay-only telecast of the 2009 Ashes series was watched by less than 30% of those who watched the terrestrial telecast of the 2005 Ashes series. Even so, Sky is making the ECB and its constituent counties financially robust and enhancing their capacity to promote grassroots cricket.

On its part, Cricket Australia is advancing the case for night Tests, to win a prime-time audience for long-form cricket. However, everybody realises the need to think beyond gimmicks. The important mission is to somehow gain access to Indian cricket audiences and pamper them.

This is beginning to happen in several ways. The Champions' League, for instance, is not a very exciting tournament for Indian audiences, especially if Indian teams get knocked out early, as happened in 2009. Before deciding on its flagship Twenty20 product for the Diwali/winter season, the BCCI considered domestic options, including a sort of IPL Lite.

| The new model, where the BCCI sells the telecast to the TV channel, had a major implication for the viewer. It reduced if not effaced the integrity and independence of the commentator. Indeed, the decline of the commentator has been the untold but unstoppable story of the decade | |||

"But other countries would have protested," says a BCCI official, "We do need them, even if we dominate the cricket business. We are giving the other boards a good part of the Champions League television revenues. This is our way of saying thank you and helping them gain from the Indian television market."

The other hook is scheduling. India and Australia propose to play each other every year, home or away, simply because this is the international cricket match-up with the most revenue potential. India's tour of Australia in 2007-08 was a money spinner. India has played Pakistan, England, New Zealand, South Africa, Sri Lanka and even Australia (in India) since then, and the numbers are there to see.

That apart, tournament organisers are starting to factor in Indian timings. Matches in England, South Africa and Dubai/the Middle East suit Indian television prime time but those in the Caribbean, in the other half of the world, don't. As such, the 2010 Twenty20 world cup, to be played in the West Indies, will see matches played in the mornings, local time. The stadium may be empty but the Indian viewer must not be inconvenienced.

It is not very different from the controversy that breaks every other Olympic Games, when some major event - the 100 metres final, a swimming final, a critical basketball game - is scheduled for a mid-morning or late-night start only because American television networks insist.

In the years to come, television channels and their obsession with Indian audiences are going to seriously challenge the idea of rotating the World Cups among Test-playing countries. Some venues may be more favoured than others.

Finally, of course, there is the attempt to clone the IPL. Australia and England are actively encouraging their state and county teams to hire Indian cricketers for domestic Twenty20 leagues. Once the global recession ends, the idea of the "Southern Hemisphere League" - featuring franchises from Australia, New Zealand and South Africa - may be revived and could hinge on teams signing Indian stars and so making themselves, and their matches, potential magnets for Indian television audiences.

How will this play out? Will top Indian cricketers - as opposed to just-retired stars - have time to spare from international commitments to make themselves available for overseas Twenty20 leagues? How will the BCCI respond to Twenty20 leagues that use Indian cricketers and exploit the Indian television market but are not controlled by the Indian board?

There's more. Will there be adequate television support for the 50-over game beyond the 2011 World Cup? Will the direct contest between that tournament, co-hosted by India, and the fourth edition of the IPL that will follow immediately afterwards see television viewers and advertisers adjudicating on the destiny of cricket? Will the Test match exist only as an occasional indulgence, the one magnum of champagne in a cellar full of lesser wines, subsidised by the revenues from Twenty20?

Watch this space in December 2019. We should have the answers.

Ashok Malik is a writer in Delhi

© ESPN EMEA Ltd.

| ||||||

| Comments have now been closed for this article |

||||||

- From Launceston to the top of the world

- A video look back at Ricky Ponting in the 2000s

- Ponting voted Player of the Decade

- Australian captain beats Jacques Kallis to be voted cricketer of the 2000s

- 'This one's extra satisfying' - Ponting

- Cricinfo's Player of the Decade title is "a great honour and a great thrill" for Australia's captain

- Laughing boy

- Like Bradman before him, Ponting turned the opposition into ball-ferriers, delighting in his mastery all the while

- Gilly and Baz go bonkers

- Flintoff's Edgbaston magic, a Tendulkar gem, that 434 chase, and the IPL's fiery start feature in the second part of our performances of the decade

- Rock-bottom RCB brace for more SRH fireworks in Hyderabad

- Pant and Axar star as Capitals cling on to win topsy-turvy thriller over Titans

- Jamie Overton back injury hands England T20 World Cup selection dilemma

- Scenarios - Can RCB still make it to the IPL 2024 playoffs?

- Hollie Armitage hundred rescues Diamonds, sees off Storm

IPLFan, I think you may be missing the point. The article highlights the fact that any franchise system would be reliant on an Indian audience - therefore if this was a substitute for current systems it would, if anything, only increase the dominance of an India market. Instead of looking for a large country like the US, the ICC must accelerate the development of the already improving Associates, thereby creating a solid bloc of non-BCCI revenue.

Posted by jamshed on (December 24, 2009, 11:51 GMT)The format of the 2011 World Cup has apparently been designed to avoid a repetition of India's first round exit in 2007.The meaningless preliminary games will go on for an eternity.India will stay in the competition for at least that long and all the advertisers and broadcasters will be happy.The only problem will be for the discerning viewer who will have difficulty in maintaining any interest.

Posted by Raghu on (December 24, 2009, 11:22 GMT)Great article and I couldn't agree more with the part about commentary for India's home matches and the IPL. The only way I can describe their method of analysis is "Commentary by idiots, for idiots". Living in the UK, we are lucky enough to see cricket from all over the world through Sky and the quality of the production and the analysis from Sky, Channel 9 and New Zealand is brilliant. The "Hear, Hear" section on Cricinfo's Page 2 is testament to the death of cricket commentary in India. Shastri is so predictable in what he will say that I can now shout out his next hyperbolic utterance before the great man himself. For the sake of the arm chair cricket fan, BCCI I beg you to loosen the strings and let the commentary teams be independent. What's wrong with a bit of good analysis and constructive critique?

Posted by Bharath on (December 24, 2009, 2:12 GMT)Nicely done article. But like BlueCat and BaijuSuper11 have mentioned, I find that you too, are ignoring the elephant in the room. Viewers are being shortchanged of the match experience by being bombarded with the worst kind of trash ever seen passing off as an advertisement. It almost seems as if these ads are designed to irritate, make us miss important moments in the match, and generally increase blood pressure. The lack of standards is appalling. Ticker-tapes belong in a News channel, not live sport. Pop-up advertisements belong on webpages (if at all!) and not on the TV. What are we to see next> Advertisement-free, premium-cost cricket channels, with real commentators, and not proxy advertisers yelling "and thats another @#$#%$ sixer."

Posted by Edward T on (December 23, 2009, 22:51 GMT)Turn the sound down on the TV and listen to the radio. At last that's how we do it in Australia. Apart from Richie Benaud, the Nine network commentary team is not worth listening to. At least with the ABC team on the radio we get to hear pearls of wisdonm from Kerry O'Keefe and the bowlologist Damien Fleming.

Posted by Pradeep on (December 23, 2009, 19:25 GMT)catch the Chinese and the Americans and the tv cricket would turn upside down....THAT is why t20 needs to b rly globalized.

Posted by Rajesh on (December 23, 2009, 18:25 GMT)Thank you for an informative article. The core message seems to be that networks and through them the viewers are dictating the terms about when, where and how the game is played. This is classic consumer driven product development. Most products come out with different versions or flavors of it original product, try to appeal to its constituent demographic and that's what's happening here. The sheer number of Indian audiance and their love and apetite for the game means they are in the driver's seat (driver's couch!). We are seeing this in cricket now. As the Indian consumer gets richer, this will start happening in other areas as well. I long to see the day when Indian consumer dictates the world economy. Some time in hopefully not too far a future...

Posted by Ravish on (December 23, 2009, 16:51 GMT)In future IPL will have a 10-week T20 tournament and a 10-week 40/40 tournament in addition to a 2-week CL in T20 and 2-week CL in 40/40s. Franchises will just sign players to full-year contracts and they will see 6-9 week window is a restriction on that expansion. If they are willing to spend $225 million plus on franchises, they would like to see fully-contracted players and longer tournaments like EPL. This will be my prediction for the next decade and we will see the players moving away from central contracts to franchise contracts and be assigned to national duty for world cups. There might be about 10 weeks assigned each year for tests where about 8 tests might get played. There will not be anymore ODIs by the end of next decade, just world cups in T20 and 40/40 format.

Posted by Ravish on (December 23, 2009, 16:25 GMT)If I am a venture capitalist now and looking to invest in Indian businesses, one of the sure things I would look at is the investment in talk radio - be it sports talk or political talk. They need to look no further than USA to see what happened there. The TV revolution took off there and eventually as the number of cars per household increased so too did talk radio as people were increasingly spending more time on the road and were held slave to their radio in the cars. India is seeing a boom in the number of new cars bought each month with each month beating the previous months purchases by a huge margin (60+%). This means going forward there is a definite market for talk radio and sports talk will have a niche loyal market of its own.

Posted by H on (December 23, 2009, 16:03 GMT)Looking at numbers above, it looks like UK board takes in about as much as Indian board. Indian board, it seems gets $175m for IPL + $27m for intl matches every year. UK board gets f75m ($100 - $125m?) from sky for intl matches and unspecified amount for county cricket. Add to that the stadium revenues, which I expect are much higher in UK and you can see they are both raking in about the same. I suspect the same is true for Aussies. However, BCCI/IPL has been very generous in sharing its revenues with players, while the British and other boards are hoarding the cash. What ECB offered to Flintoff for the whole year of cricket was less than tenth of what IPL offered him for a month and a half! That, I believe, is at the root of what makes those boards less influential.