|

Cricket's most successful variations, like Twenty20, are those that actually look more like cricket rather than less

© AFP

|

|

Twenty20 seems so fated to take over the world that it cannot be long before batsmen start hitting four4s and six6s, and falling for duck0s. But the underlying idea of making cricket faster, shorter, simpler and sillier is an old one. In fact, for a game whose commandments sometimes seem to have been handed down on clay tablets, cricket has throughout its history been interpreted with disarming freedom.

Nor should it be overlooked that the model of an 11-a-side two-innings game on which "first-class" cricket converged was only one of a host of cricket variations in use 200 years ago. Cricketers still took the field against one another as individuals, in single-wicket competition; as threes, fours, fives and sixes, in double-wicket competition - and against odds, often apparently overwhelming. When the first English team toured Australia from January 1862, it played 11 of its 14 games as XIs against XXIIs, and not until 1946-47 did English cricketers undertake an Ashes tour in which every game was on equal terms.

Sometimes the concepts combined. In one of the most famous duels, in 1810 the great allrounder William Lambert took on Lord Frederick Beauclerk and TC Howard - and won by 15 runs to claim a stake of £100. This he did, apparently, with wides, which did not then count against the bowler, and which, legend has it, drove the combustible Beauclerk crazy. There were combinations, too, that not even ECB marketers have dreamed up. Near Rickmansworth in May 1827, for example, "two Middlesex gentlemen" were defeated by Harefield farmer Francis Trumper "supported by his dog", providing a windfall for gamblers: an event of potential historical significance to Cricinfo, Coral, and Krufts.

One on one

And while odds cricket hasn't survived, except when England want to fritter a couple of days away against an Australian state, the old-fashioned head-to-head contest has shown considerable durability. In the year the inaugural one-day domestic knockout, sponsored by Gillette, was launched among the English counties, Scarborough hosted and Carling sponsored an international single-wicket competition featuring mainly county cricketers but also involving Chandu Borde and Joe Solomon.

Relocated in July 1964 to Lord's, staked by the brewer Charrington, and thrown open to a bigger field including Garry Sobers and Richie Benaud, it established a reputation for innovative cricket and surprising results. Over the next six years, the annual event attracted players of the calibre of Graeme Pollock, Rohan Kanhai, Wes Hall, Mushtaq Mohammad, Asif Iqbal, Saeed Ahmed, Bob Simpson, Bob Cowper, Keith Stackpole and David Holford, as well as almost all England's top players of the decade. The batsmen had a maximum of eight overs to bat, amid nine fielders from the MCC groundstaff, backed up by quality keepers, including John Murray and Bob Taylor.

The model of an 11-a-side two-innings game on which "first-class" cricket converged was only one of a host of cricket variations in use 200 years ago

The model of an 11-a-side two-innings game on which "first-class" cricket converged was only one of a host of cricket variations in use 200 years ago

|

A handicap was that, potentially, a game could last two balls. The shortest was at Lord's in August 1966, when Clive Radley danced out to and missed the first delivery of his county captain Fred Titmus, who then won by hitting a boundary. Games could also be fearfully one-sided. In the last final, in August 1969, Keith Boyce smashed 84 from 46 balls, then had Brian Bolus caught second ball. The sponsor then lost interest when it was merged with Bass, Mitchell & Butlers.

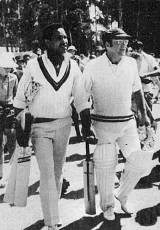

The concept excited some imitation, with a National Single-Wicket Competition for Pakistan in August 1968, won by Mohammad Siddique, and an antipodean double-wicket variation called World Cricket (Doubles) Pty Ltd, staged in Australia on three consecutive weekends two months later, won by Garry Sobers and Wes Hall. But by this stage limited-overs cricket had stolen the march on every other variation.

The one-dayer

Again, limited-overs cricket was an old idea - perhaps the oldest of all: a game, and a result, in a day. And after the success of the inaugural Gillette Cup final, England's top sports columnist, Peter Wilson of the Daily Mirror, urged the spread of the short-form game as a matter of urgency: "I am certain that if cricket as a whole ... is to have any serious spectator appeal, we must have more and more matches where a definite result can be expected and achieved within a single day ... When you come to consider it, it is as ridiculous for the man who can spare only one day at a three-day match to go there as it would be to expect him to watch only one act of a three-act play, or to read only a third of a whodunit."

Yet what's most conspicuous about one-day cricket's development is not its pace but its slowness. The counties made no immediate effort to expand the Gillette Cup, to introduce new competitions, or to take it offshore. The real initiative was shown by the International Cavaliers Cricket Club, an exhibition XI of rotating personnel devised by Denis Compton, Colin Ingleby-Mackenzie, Ted Dexter, Godfrey Evans, Les Ames, and the sports agent Bagenal Harvey. The impetus, Dexter explained, was boredom, and the "sense of frustration and futility of traveling 150 miles overnight to play county cricket in front of two men and a dog at some obscure outpost of cricket's over-expanded empire"; the rationale soon became rather more.

The Cavaliers played their first fixtures in 1963, offering their services as opponents in weekend benefit games. Then, in January 1965, their formula for 40-overs-a-side Sunday afternoon matches fitted into four hours and bankrolled by Rothmans attracted an offer for broadcast rights from BBC2. Good crowds and better ratings followed, the paramountcy of the latter acknowledged by such gestures as restricted run-ups for bowlers so that games always finished on schedule. But virtue, as they say, is its own punishment. Enviously eyeing the Cavaliers' franchise, the counties decided to muscle in, winning BBC2's patronage with a 40-overs-a-side county league sponsored by Rothmans' rival, Imperial Tobacco: thus the John Player League, a part of the English season from 1969.

|

1963: the draw for the first Gillette Cup is announced at Lord's

© The Cricketer International

|

|

Nor did one-day cricket take root elsewhere until the Australian Board of Control took the tentative step towards its own domestic knockout, staged over 40 eight-ball overs-a-side, from 1969-70. It made a faltering start - the sponsor, Vehicle & General Insurance, collapsed after two seasons, giving way to Coca-Cola, then to Gillette. But it did mean that Australians had some slight foreknowledge of one-day cricket before the

inaugural international - when, thanks to the unseasonal rain that washed away a Melbourne Test, the game's short form was fought out first by the same opponents at the same venue as was the case in the long form.

Even then, nothing happened overnight. The subcommittee deputised by the International Cricket Conference in October 1971 to discuss a cricket "World Cup" encountered resistance when it returned with the suggestion for a tournament of "Gillette Cup-style" games. The term "one-day international" was coined by Gubby Allen at the ICC meeting of 21 and 22 July 1972 even as he disdained the whole idea of them: a "World Cup" of cricket, he felt, should be "top-class games". Ultimately the Cup proceeded on a limited-overs basis because a full suite of three- and five-day games would simply have taken too long. In fact, that momentous

first World Cup final proved that one day is sometimes hardly enough, not finishing until 8.43pm.

And shorter still

To squeeze cricket into less than a day, however, has proven a greater challenge, at least without de-skilling and trivialising the game. With only ten overs-a-side, extra rewards for straight hitting, and no lbw, Cricket Max, conceived by New Zealand's Martin Crowe, was more like Cricket Min. With only eight players-a-side, and everyone but the keeper drafted to bowl two overs, the Super Eights, devised by Australian Cricket Board chief executive Graham Halbish, resembled a play without quite enough cast members.

Both were played domestically in the second half of the 1990s, then hazarded at international level. A Super Eights tournament was played in Kuala Lumpur between 12 and 14 July 1996, which an Australia A VIII won; and New Zealand beat England 2-1 in a Cricket Max head-to-head from 31 October to 2 November 1997. But the brevity of these games was, in a way, their downfall: like most things conceived purely as "entertainment", they left no trace on onlookers.

Australia and New Zealand pooled resources to create a hybrid version of their games: Cricket Super Max Eights. But you're in trouble when it takes longer to say the name of your game than to play it. Apathetic response to a tournament in Kuala Lumpur caused cancellation of similar plans in Hong Kong and Perth, and even the formal adoption of Cricket Super Max Eights as world cricket's "official third-generation game" at the ICC meeting of 23 and 24 June 1999 meant two-thirds of nought not out.

Twenty20 pays cricket three important tributes: recognising that it is a game for XIs, in which freelance fielders scarcely suffice; that equality of scoring opportunity in all 360 degrees is fundamental; and that batsmen should bat and bowlers bowl

Twenty20 pays cricket three important tributes: recognising that it is a game for XIs, in which freelance fielders scarcely suffice; that equality of scoring opportunity in all 360 degrees is fundamental; and that batsmen should bat and bowlers bowl

|

The drive to popularise Cricket Super Max Eights also kiboshed the period's other cricket diversion, the annual five-overs-a-side Hong Kong Sixes, which fell into desuetude after its sixth instalment on 27 and 28 September 1997, not resuming until 10 and 11 November 2001. Although Australians complained bitterly about the world not supporting their game, the same complaint could be made of them with regard to the Sixes, to which they've never sent a properly representative team, losing as a result twice as many games as they have won, and never improving on their second-place finish in 1994.

The quest for new variations on the game turned up some old ideas. There were several single-wicket contests, from the Courage Challenge Cup for batsmen at The Oval in September 1979 to the Silk Cut Challenge for allrounders at Arundel in September 1985 and Hong Kong two years later, plus a few double-wicket tournaments, from the Brylcreem International at Wembley Arena in April 1978 to the Pepsi International at Gaddafi Stadium in April 2001. In some ways even night cricket was a revival, given that electric-light cricket had been promoted in South Australia from 1930 by the Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia - albeit that this antique game featured underarm bowling with a tennis ball and 15-man teams.

Take it inside

Perhaps the most successful variation was the one on which authorities spent nothing. The first indoor cricket of significance occurred, improbably, in Germany: it was Husum CC, a club of minority Danes who, according to Roland Bowen, had the brainstorm of playing a tournament in a hall in Flensburg, South Schleswig, in the winter of 1968-69. Codified indoor cricket, with its dedicated courts and demarcated walls then emerged in several varieties.

In England, originally a six-a-side game, indoor cricket is thought to be the brainchild of former Worcestershire secretary Mike Vockins, who saw it as "a way of keeping enthusiasts in touch with each other during the winter months". The first league, in north-west Shropshire, was formed in September 1970; the first national competition, sponsored by Wrigleys and involving 400 clubs, culminated at the Sobell Centre in Islington in March 1976, with Durham City beating Entville in the final. By the championship of April 1979, more than 1000 clubs were involved, with Lord's Indoor Cricket School hosting the finals.

|

Garry Sobers with Eddie Barlow during his controversial appearance in a double-wicket competition in Rhodesia in 1970 © The Cricketer International

|

|

Indoor cricket in Australia has multiple parentage in one city. During the upheavals of World Series Cricket, Dennis Lillee and a club cricket colleague, Graham Monoghan, invested in a cricket school in Perth with indoor nets where they coached schoolboys, adjourning outside to play full-fledged games. "Then one day," recalls Lillee in Menace, "the rain absolutely belted down, so we decided to pull the nets back and play the game indoors. The kids loved it, we enjoyed it, and the penny dropped - maybe we should get some teams involved."

Monoghan's involvement with Lillee in indoor cricket is not as well known as their other collaboration: the aluminium bat. And perhaps more ambitious were businessmen Paul Hannah and Mick Jones, who around the same time began experimenting with an eight-a-side variation at their Subiaco Cricket Arena. Hannah and Jones later helped found the nationwide chain Indoor Cricket Arenas, and by the time the first national championships were held in 1984, there were an estimated 200,000 participants in Australia.

Indoor cricket, like squash, is held back for not being telegenic enough. The game in Australia was also bedevilled by feuding between rival control bodies, then by over-capacity when its popularity plateaued. Nonetheless Australians have dominated the confined game at international level since the first indoor World Cup was staged in Birmingham 12 years ago. Like their countrymen in the Twenty20 World Championship that concludes in Johannesburg on 24 September, Troy Gurski's Australians are red-hot favourites to continue their global interior dominance in the Indoor Cricket World Cup that finishes in Bristol on 30 September.

That Twenty20 World Championship, meanwhile, is cricket's most considerable venture since the inaugural World Cup. The game itself pays cricket three important tributes: recognising that it is a game for XIs, in which freelance or far-flung fielders scarcely suffice; that equality of scoring opportunity in all 360 degrees is fundamental to its rich variety; and that batsmen should bat and bowlers bowl - overs of filth from specialist batsmen merely look crude. This actually calls into question Twenty20's pose of being the-cricket-for-people-who-don't-like-cricket, which always made as much sense as being the music for people who prefer cacophony, or the art for people who prefer pornography. Cricket's most successful variations, it seems, are those that actually look more like cricket rather than less. There may be something to be said for this quaint old game after all.

Gideon Haigh is a cricket historian and writer